Product Innovation

This page was last edited on at

The term ‘innovation’ is often used to refer to the production of new, or changes in existing products, accessories and packaging. It includes the creation of new brands and brand variants, for example capsule cigarettes, slims, Roll Your Own (RYO), or new types of packaging. Sometimes the product remains unchanged and only the packaging is altered. It could also involve the release of new accessories, such as flavoured RYO filter tips, often in response to new regulation (see below).

Product innovation is used by tobacco companies to justify premium prices,1 circumvent and undermine regulation2, or misleadingly suggest that a product is less harmful.3

Background

In the UK, prior to 2005, tobacco product innovation was infrequent.4 The Tobacco Advertising and Promotions Act 2003, which led to the end of conventional forms of advertising in 2005. After this, product and packaging innovations, along with pricing tactics, became the only way to communicate with customers and promote tobacco products in what the industry refers to as a “dark market”.4

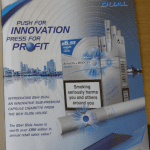

Annual reports and investor presentations of each of the four big tobacco companies reveal the importance of both product innovation and packaging innovation to the current and future success of their business.

In 2007, following their reinvention of its Lucky Strike brand in 2006, British American Tobacco (BAT) spoke about the importance of innovation in their annual report.

“Innovation is central to our continuous growth. Our growth strategy aims to generate greater consumer relevance measured by consumer demand, a reconsidered brand image, brand loyalty, willingness to pay a premium.” 5

With the introduction of further regulation in the UK, such as the Point of Sale Display Ban (POS), which came into effect for larger stores in April 2012, (with smaller stores expected to comply by April 2015) and the threat of plain packaging for tobacco products, both product and packaging innovations became more frequent, as tobacco companies attempted to popularise their brands. In December 2011, in light of the impending POS display ban, UK retail magazine, The Grocer noted that:

“the most notable trend of the past year has been an unprecedented level of new tobacco launches – everything from female-focussed super-slim and demi-slim cigarettes to flavour-changing innovations. Manufacturers are clearly in a hurry to get their NPD New Product Developments into the marketplace ahead of the display ban…” 6

Product Innovation

Cigarette additives

Tobacco companies increased the addictiveness of cigarettes by manipulating the effects of additives in cigarettes. They increased the amount of nicotine delivered to smokers; and added other chemicals (eg: flavours, sugars, ammonia) to reduce the harshness and improve the taste of cigarette smoke, and to increase the absorption of nicotine.

- See the page Addiction Manipulation for more information.

Cigarette filters

The tobacco industry uses innovations in cigarette filters as a tactic to grow sales and circumvent legislation, and to imply benefits to health.7

- See the page on Cigarette Filters for more information

Flavour Capsules

In November 2011, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) was the first tobacco company to introduce a capsule cigarette into the UK market with its Silk Cut brand variant ‘’Choice’’. Capsules are incorporated in the filter of the cigarette. They allow the smoker to release menthol flavour when they start smoking the cigarette, at some stage during the course of smoking the cigarette, or not at all.8 All four transnational tobacco companies now have capsule products for sale on the UK market, including: superslim and demi-slim cigarettes targeted at women, Roll Your Own and Make Your Own cigarettes, Additive Free Cigarettes and Miniature Cigars.

- ‘Additive free’ cigarettes in wholesome looking brown packaging, Berlin December 2012

- JTI Capsule cigarettes: Trade advert, Wholesale News June 2012

- Trade advert for Roll Your Own tobacco, Retail Newsagent 2011

- JTI Silk Cut Superslims, Bath 2011

- John player Specials Make Your Own cigarettes, The Grocer, April 2011

Concerns have been raised that consumers may believe that each of the four product innovations mentioned here convey a message of reduced risk. This is similar to the ‘light’ cigarette controversy, whereby the term ‘light’ led consumers to believe that they were smoking a reduced risk cigarette.3

In May 2020, an EU-wide ban on the sale of flavoured and menthol cigarettes, including pre-inserted flavour capsules came into force. Tobacco companies used innovations in their products, as well as newer nicotine and tobacco products and accessories, as a way to circumvent this ban and maintain a market for their products.

- See the page Menthol Cigarettes: Industry Interference in the EU and UK and Promotion of Newer Products Around The UK Menthol Ban for more information.

Menthol cigarettes are often perceived by consumers to be less risky910 There is evidence that the market for flavour capsule cigarettes has been growing in low and middle-income countries, where there may be fewer controls on the advertising and promotion of these products.1112

Similarly, there is evidence that women have considered slims to be less harmful, as there is less tobacco in each cigarette.13 RYO tobacco has been percived as more organic, with fewer chemicals and “better than cigarettes”.14 The introduction of ‘additive free’ RYO may have added to this misperception.

Packaging

In 2010, PMI attributed packaging innovation to the renewed global success of its Marlboro Gold brand which received a new brand architecture in 2008:

“The roll-out of the new Marlboro Gold packaging, present in almost 100 markets at the end of 2010, has been one of the main drivers of the variant’s success. Indeed, Marlboro Gold’s share was stable or increased in almost 70% of the top 30 volume markets in which it was present in 2010.” 15

- See the page Philip Morris’ Marlboro Brand Architecture for more information.

Public Health Concerns

There are a number of public health concerns with regards to innovation.

“Innovation can be used to undermine both tobacco tax and marketing policies and to mislead consumers into believing products may be less harmful.”1

There is a suggestion that many of these innovative products are targeted at young people and this form of marketing therefore represents a means of continuing to attract young people to take up smoking.1

TobaccoTactics Resources

- Cigarette Filters

- Menthol Cigarettes: Industry Interference in the EU and UK

- Promotion of Newer Products Around the UK Menthol Ban

- Marlboro Bright Leaf: The Pack is Important

TCRG Research

Reeves, K. Lauber, K. Hiscock, R. The ‘filter fraud’ persists: the tobacco industry is still using filters to suggest lower health risks while destroying the environment, Tobacco Control, 26 April 2021, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056245

Hiscock, K. Silver, M. Zatonski, A. Gilmore, Tobacco industry tactics to circumvent and undermine the menthol cigarette ban in the UK, Tobacco Control, 18 May 2020, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055769

Gilmore A. Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: an analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials. Tobacco Control 2012; 21: 119-26

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to the Bath TCRG’s list of publications.