Tobacco Farming

This page was last edited on at

The tobacco industry claims that tobacco farming can be a source of revenue for governments and a decent livelihood for farmers. In reality, tobacco farming often leads to economic problems, labour exploitation, environmental degradation, and health problems for farmers.

Article 17 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) encourages parties to promote sustainable alternatives to tobacco farming.1 There is a consensus that diversification programmes, designed for the local context, can improve farmers’ livelihoods.

Despite a global trend of decreasing tobacco consumption from 2000 to 2020,2 and an overall worldwide decline in tobacco leaf production during the same time period,3 tobacco remains a popular cash-crop choice for many farmers, especially in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) where the vast majority of tobacco farming takes place.45 The global fall in tobacco leaf production has been accompanied by a production shift from Europe and other high income countries, towards lower income countries like Malawi, Kenya, Uganda and Zambia367

The tobacco industry portrays tobacco farming as economically advantageous for governments and especially for farmers. Other claims include that it helps improve resilience, empowers low-income populations and strengthens communities, while the industry also tends to minimise the risks of tobacco growing for health and the environment.8910

In reality, tobacco farming often leads to economic hardships, labour exploitation, environmental degradation, and health problems for farmers. Farmers often have less influence within the political process than non-tobacco growers in the same area.11

Image 1: Tobacco leaf drying (Source: Shutterstock)

The myth of economic prosperity

According to the tobacco industry, tobacco cultivation promises high rates of return for investing in tobacco crops and long-term benefits to smallholder farmers.8910

However, tobacco growing is often less profitable for farmers than other crops, and tobacco-growing families are poorer than comparable non-tobacco-growing households.612 In Lebanon, research has shown that small scale production is so unprofitable that it would not be possible without government subsidy.13

Evidence shows that the labour costs of growing tobacco are enormous, as much as double the labour needed to produce other similar crops. For example, tobacco is amongst the most labour-intensive crops in Kenya, requiring over 1,000 hours of unpaid labour to produce one acre of tobacco.14 The number of hours needed for tobacco growing stops families spending time attaining educational qualifications or developing skills that might lead to more lucrative livelihoods.

Tobacco growing also creates specific vulnerabilities for farmers: they depend on tobacco companies for inputs and technologies, and are exposed to fluctuations in the price of tobacco leaf.15

In its reporting, the tobacco industry minimises the low rates of return on investment for tobacco growing and downplays the financial risks for the farmers. For example, BAT reported that in Kenya, tobacco farmers can either grow food for their families’ needs or have sufficient profits to purchase food.8 A 2020 study of tobacco farming in Kenya instead shows that most tobacco farmers are stuck in unprofitable ‘contract farming’ systems and 10-15% are food insecure.14

Contract farming

Most tobacco farmers work under a contract system with leaf buying-companies or directly with transnational tobacco companies like BAT.1416

Under these systems, farmers receive inputs like plants, fertiliser and machinery at the start of the season from leaf-buying companies, without having to pay for these upfront. In return, they commit to selling their tobacco to the leaf merchant. However, leaf prices are dictated by the buying companies, who often set these very low or reduce them during the contract period. Leaf buyers often use tobacco grading, or the classification of leaf quality, to reduce the offer price, often in disagreement with farmers.141718 Leaf buying companies can also deduct unfairly high costs from the payment they offer farmers, to pay back the inputs they initially provided.14

Contract farming rarely produces the high returns promised by tobacco and leaf-buying companies. Instead, contract farmers remain stuck in ‘bonded labour’: debt cycles where they never earn enough to repay their debts.14161819 Contracted farmers often have to rely on the unpaid labour of family members and children in fields in order to meet contract requirements.16

Farmers often understand that this contract system for tobacco farming is risky but agree to this work because they lack the credit to pursue other economic opportunities. Contract tobacco growing guarantees them the income, however low, that they need in order to pay for basic necessities like healthcare and education.6

The COVID-19 pandemic and profitability

The COVID-19 pandemic worsened the struggle of farmers to find fair prices for their tobacco leaf. In Malawi, farmers reported receiving less than half of the expected rate for their tobacco leaf at auction.20 Fears that crowded auction floors and direct contact between growers and buyers would promote transmission of the virus prompted Zimbabwean authorities to delay the opening of the tobacco market selling season.2122 Once the markets did open, new regulations stated that individual farmers would not be allowed onto auction floors where they could observe buyers; tobacco association representatives would instead sell leaf on behalf of farmers.22

- For more information on the tobacco industry and COVID-19, see our page on COVID-19

The climate crisis and profitability

The climate crisis in tobacco-growing regions makes profits from tobacco growing more unreliable.

In Zimbabwe, shorter and more erratic rainy seasons decrease the quality and quantity of tobacco crops, especially for smallholder farmers who can’t afford irrigation systems and rely on rainfall instead.23

In the tobacco-growing region of Temanggung, Indonesia, the phenomenon of late tobacco harvesting seasons has become increasingly common. In this region, farmers have been losing income, as companies purchase tobacco leaf from other regions where harvesting happens earlier in the year.24

Farmers in tobacco growing regions that are heavily impacted by the climate crisis have been developing adaptation and mitigation strategies to maintain the profitability of their tobacco crops, such as irrigation systems and later harvesting. However, research indicates that “even with these adaptations tobacco and maize are riskier crops to grow than traditional grains.”2325 soil degradation,2627 biodiversity loss,28 the use of pesticides,2930 and adverse effects on farmers’ health.31 Despite this, tobacco companies use ESG rankings and accreditations to clean up their image.32

- For more information, see the page Tobacco and the Environment

Image 2: A farmer carrying a bundle of tobacco leaf (Source: Shutterstock)

Vulnerable communities

Together with the narrative of economic prosperity comes the myth that impoverished and vulnerable communities are empowered. Philip Morris International (PMI) published a report in April 2020, focusing on the empowerment of women for change in its supply chain. In this report, PMI argued that it works to “empower women to play an active role in improving the household economic condition but also in enhancing the overall wellbeing of their children and maintaining a safe work environment” on tobacco farms.33 However, a study in Zimbabwe concluded that women in households growing cash crops, in particular tobacco, were more likely to be disempowered.34 A study conducted in China, Tanzania and Kenya concluded that few women in tobacco growing households in Tanzania and Kenya had any financial decision-making power. Women also face particular harmful effects to their health while working on tobacco farms, including the risk of miscarriage while pregnant.35

All four transnational tobacco corporations present a strong and compelling narrative around tobacco farming: that it will improve livelihoods, strengthen communities, provide good working conditions and deliver financially stable futures for farmers.36373839 For example, Japan Tobacco International (JTI) states on its website that “Growers know they will receive meaningful support that not only leads to improved yields and profits, but that also help improve the social conditions and quality of life in their communities.”40

However, a WHO report on tobacco and the environment published in 2017 found that the long-term consequences include “increased food insecurity, frequent sustained farmers’ debt, illness and poverty among farmworkers, and widespread environmental damage”.17 Tobacco farmers end up having to dedicate intensive labour hours to produce tobacco leaf, in inadequate working conditions, with low wages and unfair conditions that include child labour (see below).

- For more information on the tobacco industry narratives around farming see International Tobacco Growers Association

Health risks to farmers

Tobacco leaf production has many health risks, which are frequently underreported by the tobacco industry.

According to the World Health Organization, “each day, a tobacco worker who plants, cultivates and harvests tobacco may absorb as much nicotine as found in 50 cigarettes”.5 Nicotine poisoning, also known as green tobacco sickness, occurs as a result of exposure to wet tobacco leaves during tobacco cultivation. Children are more likely to develop green tobacco sickness, not only because they have a relatively smaller body size, but also because they have not yet built up the nicotine tolerance which is needed protect them from these side effects.8 Avoiding nicotine poisoning when working with tobacco plants is difficult, even when wearing protective equipment. BAT reported several cases of green tobacco sickness in its Brazilian farming operations, despite workers having worn protective equipment.8

Another risk resulting from tobacco farming is the exposure to agrochemicals, including pesticides. Researchers found that in Kenya, 26% of tobacco workers showed symptoms of pesticide poisoning;41 in Malaysia, this number was higher than a third.42 In Bangladesh, where weed killer is frequently used in tobacco fields, significant levels of chemicals were also detected in local water sources, killing fish and soil organisms needed to maintain soil health.43

The risk of exposure to agrochemicals is generally lower for tobacco farmers in high-income countries than in LMICs, where the regulation of chemicals tends to be weaker.26 Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) plus eleven other persistent organic pollutants used in agrochemicals are banned in high income countries, but not in some LMICs.2644 Pesticides are often sold to tobacco farmers in LMICs without proper packaging or instructions.2644 The health effects that derive from chronic exposure range from birth defects and tumours to blood disorders, neurological diseases and depression.2644 Even tobacco workers who do not directly mix or spray chemicals, like harvesters, can be exposed to significant levels of toxins and are susceptible to pesticide poisoning.17

Child Labour

Child labour is a prevalent and long standing issue in the tobacco farming sector.45

Children involved in the growing stages of tobacco farming take part in labour-intensive activities,46 which poses risks to their health,4748 and limits their access to education.4950

Children working in tobacco farms are also more vulnerable to the health risks than adults, including the impacts of absorbing nicotine.51

Many of the children working in tobacco fields in Kenya report handling fertilisers and chemicals, endangering their health.1451

Tobacco farming and the FCTC

The World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) is an international treaty that aims to reduce the demand and supply of tobacco.

It recognises that as countries and governments adopt measures to reduce the demand of tobacco products, they must also address the consequences of this demand reduction on tobacco farmers who rely on these crops for their livelihoods.52

Specifically, article 17 recognises the need to:

“promote economically viable alternatives to tobacco production as a way to prevent possible adverse social and economic impacts on populations whose livelihoods depend on tobacco production.”1

The tobacco industry argues that tobacco control policies threaten the economic benefits that it claims tobacco growing brings to local farmers.1However, other crops can provide much more sustainable alternatives. In addition, demand reduction happens slowly, allowing farmers to diversify their crops gradually, reducing the economic impact.1

Parties to the WHO FCTC also have an obligation to:

“have due regard to the protection of the environment and the health of persons in relation to the environment in respect of tobacco cultivation and manufacture within their respective territories.” 52

- For more information see the page on Tobacco and the Environment

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental, Social and Governance

In response to increasing scrutiny over environmental degradation and the use of child labour in the tobacco supply chain, transnational tobacco companies have invested in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) initiatives which they describe to their shareholders in their Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) reports.32

- For more information, see the pages on CSR: Child Labour, and the Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco-Growing (ECLT) foundation

The tobacco industry has also been involved in CSR programmes supporting farming diversification in tobacco growing regions, despite the FCTC specifically recommending that “policies promoting economically sustainable alternative livelihoods should be protected from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry”.153

PMI’s ‘Agricultural Labour Practices’ (ALP) Programme

On 10 December 2020, PMI published an article seeking to celebrate the International Day of Human Rights by promoting its achievements around its Agricultural Labour Practices (ALP) program. This programme was created by PMI in 2011, seemingly aiming to end child labour and protect workers’ rights and livelihoods.54

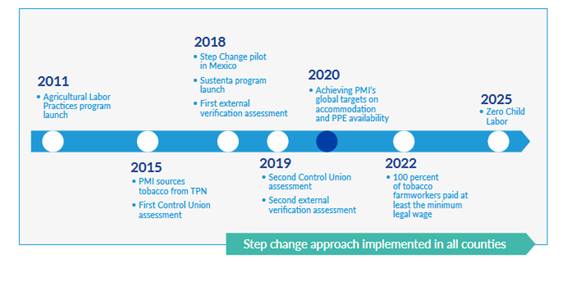

According PMI’s ALP 2020 report, the key principles of the programme include “no child labor, no forced labor or human trafficking, fair treatment, safe working environment, fair income and work hours, freedom of association, and terms of employment”.55 However, the timeline below (Image 3) from the same report, shows how, despite the programme having run for 9 years, PMI continues to use child labour in its supply chain. The company has given itself a further 5 years to end the practice.55

Image 3: Timeline of the ‘Agricultural Labor Practices Program’ (Source: Philip Morris International, ALP program 2020 report)55

- For more information on PMI’s ALP programme, and how tobacco companies fail to properly measure or manage the effectiveness of this type of initiative, see CSR: Child Labour

TobaccoTactics Resources

- Greenwashing

- Tobacco and the Environment

- CSR: Child Labour

- Tobacco Supply Chain Database: addressing the supply side of the tobacco epidemic

Relevant Links

- TCRG blog Supplying the deadly tobacco industry

- WHO World No Tobacco Day 2023: Grow food, not tobacco includes a myth buster on Tobacco growing

- WHO report: “Tobacco and the environment”

- Tobacco Atlas

TCRG Research

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including TCRG research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to the Bath TCRG’s list of publications.