Influencing Science

This page was last edited on at

Background

The tobacco industry has a long history of attempting to influence science in order to cast doubt on evidence showing the harms of its products and to argue against the need for regulation of those products. In the 1950s when science began to establish a causal link between smoking and cancer, the industry mobilised to cast doubt on that evidence. In the 1980s and 1990s, when it became clear that second-hand smoke was harmful, the industry funded and created science that attempted to obscure that harm.1 More recently, the tobacco industry has funded research in to newer tobacco and nicotine products and concerns have once again been raised that the industry is manipulating science for its own benefit.

Industry strategies for influencing science

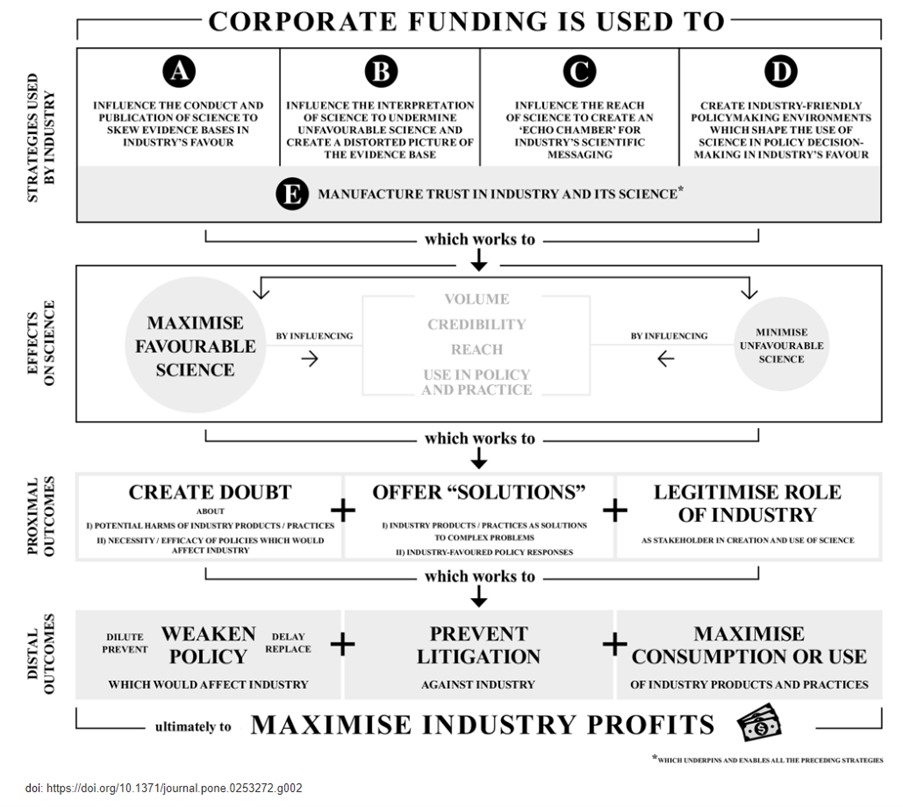

Researchers from the Tobacco Control Research Group at the University of Bath have developed a typology and model – the Science for Profit Model – to explain how and why the tobacco industry (along with other harmful industries) attempts to influence science.2 The authors conclude that strategies for influencing science are used to “purposefully-create misinformation, doubt, and ignorance”, to “obscure the harms of industry products and practices” and to “oppose regulation that could threaten corporate profits”.2

Below is an overview of this research, illustrating the ways in which the industry (and third parties used by the industry) uses science to further its aims. The following strategies and examples are drawn from the Science for Profit Model.

- To find out about these strategies in more depth, see the research paper on the Science for Profit Model.2

The Science for Profit Model

The Science for Profit Model2

Strategy A – Influence how science is conducted and published to skew evidence in industry’s favour

The tobacco industry has used various strategies to influence which research is – and isn’t – undertaken and published, in order to counteract independent scientific research which might show industry products and practices in an unfavourable light.

These strategies include funding research by third parties to deflect attention from industry harms. One example is research that looked for alternative causes of cancer (including hormones and nutrition) to distract attention from the link between smoking and cancer. This was conducted through the Tobacco Industry Research Committee from the 1950s onwards.3 Another example is research that focused on issues of “indoor air” (such as dirty air filters) to deflect attention from the harms of passive smoking, conducted through the Center for Indoor Air Research in the 1980s. Since 2017, research funded by PMI through the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (FSFW) has similarly distracted attention from industry harms, including by redirecting blame towards the public health community and the media, implying that they are responsible for a slowing in the decline of smoking rates.4

Other strategies include undertaking “risky” research secretly, so that it can be hidden or abandoned if results harm the industry’s interests,2 and manipulating study design or statistical analyses to ensure favourable findings. Another is to ‘cherry-pick’ (select the most favourable) papers to include in literature reviews to obscure parts of the evidence base.2

To see how study design affected PMI-funded science on plain packaging of cigarettes visit the Ashok Kaul and Michael Wolf pages.

In order to influence what research is published, the industry has created its own journals, such as the “Tobacco and Health” research journal which was distributed to health professionals.52 More recently, it has published in journals with editorial staff who have links to the industry, and used ‘pre-print’ platforms to self-publish its own non-peer-reviewed science.46

- For more examples of how the tobacco industry influences the conduct and publication of science visit Influencing Science Case Studies

Strategy B – Influence how science is interpreted to undermine unfavourable science and create a distorted picture of the evidence base

The industry also works to distort how science and scientists are seen by the public and experts.

In the 1990s, tobacco companies launched the “Sound Science” and “Good Epidemiology” public relations campaigns. These demanded unrealistic levels of evidence in epidemiological studies examining harms caused by industry products, and were designed to prevent policy action on passive smoking.2

For decades, the industry has attacked and misrepresented science and scientists that may harm its commercial agenda. For example, in the 1990s, it criticised a US Environmental Protection Agency risk assessment which concluded that second-hand smoke was carcinogenic.2 Nearly thirty years later the director of the Centre for Research Excellence: Indigenous Sovereignty and Smoking (COREISS), an FSFW grantee, used a similar argument, despite overwhelming evidence that second-hand smoke is a health risk:

“scientific studies have not proven that exposure to cigarette smoke in the car causes disease”.47

In the 1990’s Philip Morris developed plans for what it called “Project Sunrise” – a project in which the company proposed the monitoring of individuals and organisations working in tobacco control, framing some as “extreme” and others as “moderate” in order to divide the community.8 Some of the many attacks on individuals working in tobacco control are documented on Martin Cullip, FOI: Stirling University and FOI: University of Bath.

- For more examples of how the tobacco industry influences the interpretation of science, visit the Influencing Science Case Studies page.

Strategy C – Influence the reach of science to create an “echo chamber” for industry’s scientific messaging

The industry disseminates messages that support its scientific stance. A common approach is to contract third party “friendly” voices to amplify scientific messages and distance these messages from industry. These messengers include front groups, designed to look like unbiased sources, organisations such as think tanks and professional associations, and “expert” individuals.2

In the 1980s, the ‘Whitecoat Project’ was Philip Morris’s secret plan to recruit ostensibly independent scientists to disseminate scientific narratives which would help it to “restore the social acceptability of smoking”.2 Read more about the project on the Influencing Science: The Whitecoat Project page.

Organisations funded by FSFW have promoted industry-friendly scientific narratives on e-cigarettes and COVID-19, and endorsed science calling for weaker regulation of the industry’s products.4

In order to maximise press coverage of industry-favourable scientific messaging, the industry funds media outlets to disseminate its science, cite its staff, and report on its scientific events, including conferences.910 One example is Filter magazine – to find out more visit the page on The Influence Foundation.

- For more examples of how the tobacco industry uses third parties to spread its scientific messages, visit the Influencing Science Case Studies page.

Strategy D – Create industry-friendly policymaking environments which shape the use of science in its favour

Tobacco companies have worked to embed their own standards of evidence in policymaking, and bring about policy reforms that increase reliance on the tobacco industry’s own science.2

In the 1990s, the tobacco industry attempted to shape risk assessment of its own products, and influence European Union (EU) regulatory mechanisms in relation to the assessment of data from epidemiological and animal studies, for example. Although they did not succeed, this would have meant that the criteria used for determining scientific ‘proof’ would have been drawn up by industry itself.2

British American Tobacco promoted regulatory reform in the EU, to make it harder to implement public health policies which conflicted with its commercial interests. This ‘Better Regulation’ or ‘Smart Regulation’ appeared to be about good governance and transparency but “in fact mandated industry’s right to be heard early in scientific debates about their products and practices.”2 Read more on this topic on the EU Better Regulation page.

Strategy E – Manufacture trust in industry and its scientific messaging

The industry has worked to promote its involvement in science in order to manufacture an image of scientific credibility. Many academic institutions and journals no longer collaborate with the industry directly, due to its history of scientific deception, and so the industry uses third party organisations to push for ‘renormalisation’ of its business.1112 For instance, since it was set up in 2017, FSFW has worked to frame the industry’s involvement in science and policy as the ‘solution’ and its exclusion as counterproductive, despite industry having created the problem.4

At other times the industry does not disclose its involvement in science when it believes this will lend the science more credibility. Sometimes it creates third party organisations that appear to be independent, to conduct its research (e.g. Philip Morris setting up the Institute for Biological Research in Germany).13 At other times it uses public relations consultancies and law firms to recruit scientists.2

- For a more extensive overview of industry allies and front groups see the Industry People and Allies topic as well as the Allies Database produced by Stopping Tobacco Organizations and Products (STOP)

Desired outcome of influencing science

The desired outcome for the tobacco industry has been to create doubt about the harms of its products, or about the necessity – or efficacy of – tobacco control legislation. It has framed use of its newer products as the only realistic solution to the tobacco epidemic, and aimed to legitimise its role as a stakeholder in science and policymaking.2

These outcomes weaken policy that would reduce industry profits, prevent litigation against the industry, and maximise consumption of its products. In short, the industry’s involvement in science does not primarily advance knowledge or improve the health of populations, but maximises profits.2

Influencing Science Case Studies

For more detailed historical and contemporary examples of how tobacco companies influence science visit Influencing Science Case Studies.

Tobacco Tactics Resources

- Influencing Science Case Studies

- Influencing Science: Philip Morris Changing the Conclusions of Research

- Influencing Science: Ghost Writing

- Influencing Science: Imperial Tobacco Canada

- Influencing Science: The Whitecoat Project

- Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products

- Industry Approaches to Science on Newer Products

- COVID-19

- Tobacco Company Investments in Pharmaceutical & NRT Products

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

- Tobacco Industry Research Committee

- Forest

- Duke University

- Tobacco Industry Research Committee

- Tobacco Institute

- Hill & Knowlton

- Ruder Finn

See the list of pages in the category Influencing Science

TCRG Research

The Science for Profit Model—How and why corporations influence science and the use of science in policy and practice, T. Legg, J. Hatchard and A.B. Gilmore, Plos One, 2021, 16(6):e0253272, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0253272

Document analysis of the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World’s scientific outputs and activities: a case study in contemporary tobacco industry agnogenesis, T. Legg, B. Clift, A.B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2023, doi: 10.1136/tc-2022-057667

Paying lip service to publication ethics: scientific publishing practices and the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, T. Legg, M. Legendre, A. B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control 2021;30:e65-e72, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056003

Seeking to be seen as legitimate members of the scientific community? An analysis of British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International’s involvement in scientific events, B. K. Matthes, A. Fabbri, S. Dance, L. Laurence, K. Silver, A. B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2023, doi: 10.1136/tc-2022-057809

Tobacco industry messaging around harm: Narrative framing in PMI and BAT press releases and annual reports 2011 to 2021, I. Fitzpatrick, S. Dance, K. Silver, M. Violini, T. Hird, Front. Public Health, 2022, 10:958354, doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.958354