Racism and the Tobacco Industry

This page was last edited on at

In 2016, tobacco companies were faced with a new law in the UK which would force them to introduce plain packaging on their products. The industry reacted furiously. Front groups sent letters, bogus reports were commissioned and a legal action was launched. How could they be treated like this, wailed the lawyers for British American Tobacco. And if plain packaging was going to happen, then they wanted compensation. The precedent they drew upon was the compensation paid to slave owners by the British government after the abolition act of 1833. The tobacco companies asserted the brands were their property and wanted recompense – just as slave owners had been given. It was an argument dismissed by the court and an ironic one at that.12

It was also an unwitting reminder by tobacco companies of their deep and troubling ties to slavery. The vital role slavery played in establishing the wealth of the sector is well-understood,3 though not if you look on tobacco company websites.

“There is a line of heritage and practice that runs from 17th century slave-trading merchants to modern-day tobacco companies.”

The Imperial Brands website explains the company’s origins. Imperial grew out of the Wills company, founded in Bristol in 1786. “Wills was known for its family spirit and a belief that workers should enjoy themselves,” it proudly says.4 The Wills company has been accused of profiting from slave produced tobacco.5 On the opposite side of the Atlantic other tobacco businesses, such as RJ Reynolds, now part of British American Tobacco (BAT), grew out of slave owning, tobacco farming families.6

But exploitation and colonial practices by the tobacco industry are not relegated to history. The global tobacco trade is still largely run by companies in Europe and the USA that have been accused of exploiting cheap labour and weak regulations in low- and middle-income countries.7 They also stand accused of employing racially predatory marketing; for decades Black Americans have been targeted by menthol cigarette advertising.8 There is a line of heritage and practice that runs from 17th century slave-trading merchants to modern-day tobacco companies.

Roots in slavery

From the late 1600s, Bristol, where Imperial Brands is still headquartered, became involved in the production of tobacco on Virginia plantations. While initially the crop had been produced by indentured white labourers, African slaves soon became a cheaper alternative.9

Supporting the transatlantic slave trade were tobacco merchants and investors in England. Bristol was a hub for both slave ships and the tobacco and sugar trades.10 One well-known Bristol figure at the time was Edward Colston.11 According to Bristol Museums “Edward Colston never, as far as we know, traded in enslaved Africans on his own account […] What we do know is that he was an active member of the governing body of the [Royal African Company (RAC)], which traded in enslaved Africans, for 11 years.”12 In his role Colston “played an active role in the trading of over 84,000 enslaved African people (including 12,000 children) of whom over 19,000 died on their way across the Atlantic.”13 Those transported were enslaved on American tobacco and sugar plantations.1114

Colston’s statue was torn down in the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 and thrown into Bristol harbour where slave ships once docked. Despite the lives destroyed by his trafficking, Colston’s philanthropy earned him admiration in the city. The plaque that remains on the empty pedestal describes Colston as “one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city.” To this day, tobacco company philanthropy is employed to distract from the lives lost to the trade.

The Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, established by Royal charter in 1660, eventually became the Royal African Company (RAC), receiving an official charter to conduct slaving operations in 1672.15 From then on the RAC maintained a military presence in Africa, controlled the shipping of people and goods, answered to a headquarters in London and deployed a network of agents to maintain its monopoly.16 There are parallels to be drawn between the RAC and British American Tobacco (BAT), formed in 1901 and still dominant in Africa and many other parts of the world, where it often acts with the quasi-support of the British government.17

Colonial operations

BAT continues to operate with a colonial mindset, according to African tobacco control activists like Dr. Yussuf Saloojee. He is a former director of the National Council Against Smoking, a South African-based NGO pressing for African governments to launch criminal investigations into BAT and its alleged continued involvement in cigarette smuggling. Saloojee says of BAT: “The days when they can march in with their colonial arrogance and treat Africa like some lawless frontier are over[…] Africa has enough problems without multinational corporations undermining the stability of our governments and national policies.”18 BAT has also been accused of using bribes to undermine the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in East Africa. At the time, BAT told the BBC: “We do not and will not tolerate corruption, no matter where it takes place.”19

The leadership structure of BAT, Philip Morris International (PMI), Altria and Imperial Brands are also reminiscent of their colonial past. From headquarters in the tobacco plantations of the USA and ex-imperial centres of Europe, they control the global tobacco trade, having bought up smaller, regional companies. Executives and directors are almost exclusively White European or American posted to South East Asia, North Africa, West Africa or South America to run local operations.202122 Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) suffer most from this familiar system, where an industry born of Empire imposes its destructive business on less powerful nations. Cigarette consumption and associated mortality is now higher overall in LMICs and growing, thanks to aggressive marketing, and cheap labour that is frequently exploited.23 Fear of improvements to labour and tobacco marketing laws means tobacco companies often interfere in the governance of these regions, echoing the history of empire and colonial control.

Tobacco company exploitation in Africa is apparent in the mounting accusations of child labour on tobacco farms. In Malawi, the British legal firm Leigh Day is representing farmworkers in a lawsuit against British American Tobacco and Imperial Brands for the “widespread use of unlawful child labour, unlawful forced labour and the systematic exposure of vulnerable and impoverished adults and children to extremely hazardous working conditions”.24 In Zimbabwe, child labour and human rights abuses occur on tobacco farms25 and in Zambia, farmers risk COVID-19 to boost Japan Tobacco International profits.26 The industry’s response to criticism over these abuses is to fund a front group that has achieved little in reducing child labour.27

Racist marketing

Modern day exploitation also extends to the consumer. In the US, companies use predatory marketing to target Black customers with menthol cigarettes,288 worsening the disproportionate health harms to Black communities from smoking. Meanwhile, they preach support for Black Lives Matter and racial justice. In June 2020, Altria announced it would provide $5 million to “fight racial inequality”.29 In contrast, leaked company documents from the year 2000 reveal plans to specifically target African American and Hispanic leaders as part of an image rebrand called PM21, describing these leaders as “influential on political thinking.” and saying “We need to develop relationships with them and ‘educate’ them.”.30

Kool Menthol (1981)

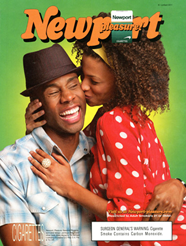

Newport Menthol (2005)

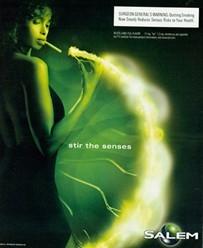

Salem Menthol (2004)

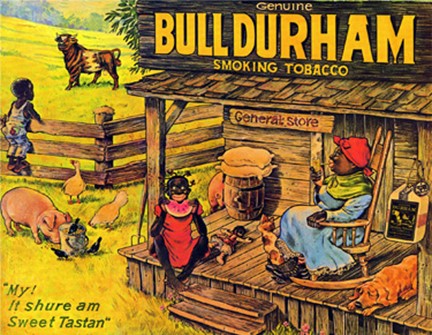

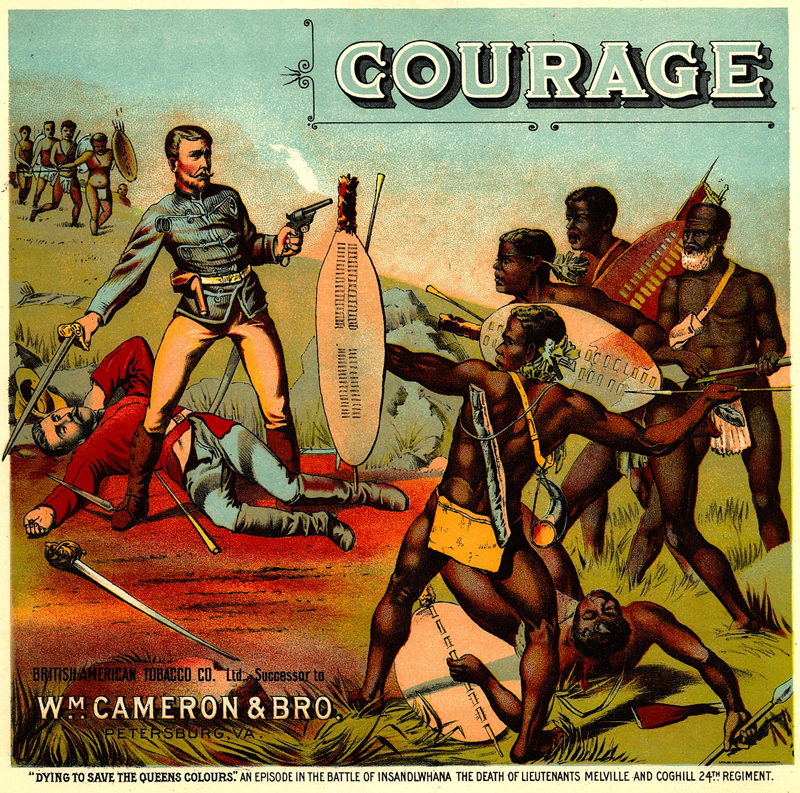

The industry’s efforts to target Black consumers began after the Second World War, as communities became more urbanised and increased in spending power.31 Prior to WW2, advertisements featured deeply racist and imperialist imagery to appeal to white consumers. Stanford’s tobacco marketing archives give an idea of the range of offensive material produced.32

Bill Durham Tobacco (1900)

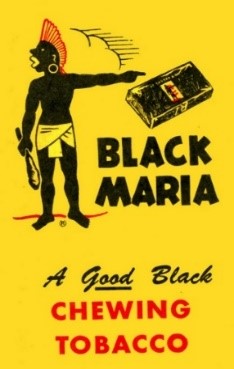

Black Maria Chewing Tobacco (early 20th century)

Courage Tobacco (1930)

Red Man Snuff (2008)

It is not just the Black community that is subject to racist exploitation by tobacco companies. Experts on US public health racial disparity, D’Silva, O’Gara and Villaluz, write: “The tobacco industry has misappropriated culture and traditional tobacco by misrepresenting American Indian traditions, values and beliefs to market and sell their products for profit.”.33 One of the first products to exploit Native American identity was Red Man Chewing Tobacco, introduced in 1904 by Pinkerton Tobacco and still sold today by Swedish Match.34 In response to criticism, one cigarette manufacturer highlighted how much money they gave to Native American charities and the free tobacco offered for ceremonial purposes: “We’d like to think that we’re giving something back to these people in exchange for using this imagery,” Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company (now owned by BAT) wrote in a briefing note.35 Meanwhile, cigarette company identity is often based on colonial imagery. The branding is designed to evoke a fantasy of benevolent rule and status from a time where tobacco companies were making major profits off the back of slavery and brutal empire building. The name Imperial Brands (formerly Imperial Tobacco) is an obvious example, as are brands like Colonial cigarettes sold by British American Tobacco in Belize.36

“No cigarette company has been held accountable for its history of targeting minority communities and the disproportionate health harms inflicted.”

Tobacco companies are not the only ones to have used racist and imperialist iconography. However, while brands such as Quaker Oats and its Aunt Jemima syrup have pledged to remove racist stereotypes, no cigarette company has been held accountable for its history of targeting minority communities and the disproportionate health harms inflicted. Ethnic minorities in the USA and Europe are more likely to die of smoking related diseases than the White population and this disproportionate suffering is now magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic.373839

Corporate social responsibility and race

Rather than confront a history of colonialism and racism, Big Tobacco uses philanthropy and corporate social responsibility (CSR) programmes to distract from past and present misdeeds. Third-parties or front groups are employed to create the façade of independent and influential support.

For example, there is emerging evidence that Philip Morris International has begun recruiting cultural influencers to its PR “communications platform”, Mission Winnow.40 This move is reminiscent of the aforementioned PM21, when the company sought to target “civic leaders, women and minority communities.”.41

Another group wholly funded by PMI, The Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, has suggested a ban on menthol cigarettes would cause Black Americans to be targeted by police.42 Tobacco control advocates Sandra Mullin and Dr Mary Bassett say this is “perverse logic”: smoking kills, and menthol cigarettes kill far more Black people.43 As the history of police brutality against Black Americans can attest, police officers do not wait for a whiff of menthol smoke to employ violence. In response to marketing that targets Black communities, activists have joined force with the American Medical Association and are suing the FDA to ban menthol cigarettes.44

The tobacco industry is rooted in the Atlantic slave economy and while this may have ceased, the exploitation of Black communities and low- and middle-income countries continues. Any tobacco industry outreach in the name of racial justice is disingenuous if it refuses to face up to historical transgressions, continues to exploit tobacco workers and targets its deadly products at Black and other minority communities.

Authors

Phil Chamberlain, Nancy Karreman and Louis Laurence.

With thanks to Michél Legendre from Corporate Accountability for his assistance with this article.

Go further

If you wish to explore this issue in more detail the following resources are useful:

Watch the University of Bath film Tobacco Slave

STOPPING MENTHOL, SAVING LIVES ENDING BIG TOBACCO’S PREDATORY MARKETING TO BLACK COMMUNITIES

Community-Led Action to Reduce Menthol Cigarette Use in the African American Community

Menthol-Flavored Tobacco Products

Why tobacco is a racial justice issue

The Black Community: A Target for the Tobacco Industry Since Slavery

Ghosts of Bristol’s shameful slave past haunt its graceful landmarks