Price and Tax

This page was last edited on at

Key Points

- Taxation is the single most effective public health measure to reduce tobacco consumption and disease

- Tax-related price increases reduce affordability, and so reduce smoking rates and smoking intensity

- The impact is greater for lower income groups who are most at risk from smoking-related harms, and more effective for youth

- Tax increases are a predictable and reliable way for governments to raise revenue

- Tobacco companies use a range of pricing strategies to undermine the beneficial effects of tax increases

- Industry interference with taxation policies is well-documented

Why tax tobacco products?

Taxation on tobacco products is by far the most effective and cost-effective public health measure to reduce tobacco consumption and related morbidities (illnesses or diseases).1 Increases in prices, as a result of significant increase in tobacco excise taxes, are known to reduce affordability – and therefore also tobacco consumption – faster than any other single measure.2 Taxation of tobacco products is considered a very important ‘win-win’ policy as it not only promotes health but is also an efficient way to increase government revenues.

Economic benefits

The World Health Organization (WHO) considers this a “best-buy” intervention as benefits are several times higher than its cost.3 Taxing tobacco products is one of the least costly of all tobacco control policies, costing US$ 0.05 per capita per annum to implement in a LMIC.14 Taxes can also be earmarked for public health programmes and services, including combating diseases for which tobacco use is a significant risk factor, including noncommunicable diseases, cancers, and diseases of the blood vessels of the brain, such as stroke and haemorrhage.

Health benefits

Increased excise taxes on tobacco have been found to significantly reduce smoking rates as well as smoking intensity (number of cigarettes consumed per day).5 On average, a 10% price increase will reduce consumption by at least 5% in low and middle-income countries (LMIC) and as much as 8% in some. In high-income countries the reduction is about 4%.26 This leads to improved health and productivity, and prevents premature deaths. It encourages current smokers to quit, prevents former smoker from restarting, and discourages vulnerable populations, especially youth, from experimentation and initiation of regular smoking.789

Increased price has a greater impact on lower socio-economic groups and therefore helps to reduce health inequalities.10 This is because the costs and health burdens of smoking are disproportionately higher for low-income people, who are also more likely to smoke and less likely to have access to health care. Since they are especially responsive to price increases, they are more likely to stop or reduce their smoking as the price goes up. Therefore, in terms of health, they potentially benefit the most from higher excise taxes.11

FCTC Article 6: Good practice in tobacco taxation

The Article 6 of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) on ‘Price and tax measures to reduce the demand for tobacco’, commits parties to using tax and price policies to reduce tobacco use. All parties to the treaty have an obligation to implement tax and price policies. Information on parties’ progress can be found on the FCTC implementation database.

In order to aid parties with their implementation, guidelines were adopted by the Conference of the parties (COP) at its sixth session in October 2014.12 The guiding principles of Article 6 are as follows:12

- Determining tobacco taxation policies is a sovereign right of the Parties

- Effective tobacco taxes significantly reduce tobacco consumption and prevalence

- Effective tobacco taxes are an important source of revenue

- Tobacco taxes are economically efficient and reduce health inequalities

- Tobacco tax systems and administration should be efficient and effective

- Tobacco tax policies should be protected from vested interests

Research by Tobacconomics on a variety of tobacco taxes and tax structures around the world has informed WHO advice on best practices for an effective tobacco taxation policy.1314

As more and more countries are adopting policies to raise their levels of taxation, as of 2020 one in five countries are now protected by high tobacco taxes.15 However, only 40 countries (where 13% of the world’s population resides) were able to increase their taxes to best-practice levels i.e., at 75% or more of the price of the most popular brand of cigarettes. For more details see the FCTC implementation database.

The tobacco industry response to tax

The tobacco industry is fully aware of the massive impact of tax increases in driving down consumption, as shown by multiple internal industry documents reviewed over decades.16

In 1983, Philip Morris in Australia stated:1718

“…The most certain way to reduce consumption is through price.”

Then again in 1985:

“…Of all the concerns, there is one – taxation – which alarms us the most. While marketing restrictions and public and passive smoking do depress volume, in our experience taxation depresses it much more severely. Our concern for taxation is, therefore, central to our thinking about smoking and health. It has historically been the area to which we have devoted most resources and for the foreseeable future, I think things will stay that way almost everywhere”.

And in 1993:

“…A high cigarette price, more than any other cigarette attribute, has the most dramatic impact on the share of the quitting population”.

The strategies that the tobacco companies employ to circumvent and undermine tax policies are well established, and include legal challenges, direct lobbying and indirect interference via third parties. They have successfully used arguments which exploit concerns around the political economy of taxation.14 At the same time they have also been found to be complicit in tax avoidance, smuggling and bribery.

- For details see: The Tobacco Industry and Tax

Types of taxation

Taxes levied on tobacco products include consumption taxes and import duties. Excise, and sales taxes (e.g., value added taxes, or VAT) are the most common forms of domestic consumption tax. Many countries apply different types of these taxes and/or differing rates of such taxes on different types of products, for example factory made cigarettes vs. bidis.

Excise taxes

These are the taxes that are applied on selected commodities such as tobacco, alcohol, and fuel. Excise taxes have great potential public health impact (by reducing consumption) as they constitute a greater share of prices in most countries. They also generate more government revenues. There are two types of excise taxes: specific and ad valorem.

Specific vs ad valorem

A specific excise tax is levied based on quantity or weight of tobacco products (e.g., a pack of 20 cigarettes or tax per 1,000 cigarettes). It is a more stable and predictable source of revenue than ad valorem tax and relatively easier to administer. Crucially, specific taxes raise the prices of all brand categories simultaneously, so does not magnify existing price differentials (the difference between the cheapest and most expensive brands), as ad valorem taxes do. The industry tends to promote higher priced, premium products as it profits more from these. An increase in the specific tax rate reduces the risk of consumers substituting higher-priced brands with lower-priced brands.19 However, if specific taxes are not regularly adjusted, the real value of excise will fall with inflation.20 This is why some countries (e.g. Australia) commit to yearly adjustments for inflation, or a broader tax escalator, that increases taxes by inflation plus an additional amount (e.g. the UK).

An Ad valorem excise tax is levied based on a percentage of the value (e.g., a percentage of the factory price as in China, or of the retail price as in Bangladesh and Turkey). These taxes generate unstable and less predictable revenues and are more difficult to administer compared to specific taxes, as they require strong tax administration and technical expertise. As ad valorem tax is based on the price of the products, it can therefore lead to greater price differentials between products. It can also result in a reduction in revenue due to consumers switching to lower priced products or brands, a practice called ‘downtrading’. One benefit is that it automatically adjusts to inflation and industry price rises, as the real value of taxes will be preserved whenever prices increase.

In some countries the excise tax varies by tiers and is complex or multi-tiered depending on the defined characteristics of products. These can include price level, type of production, type of package, length of cigarettes (India, Sri Lanka) and filtered or unfiltered cigarettes (Russia).21 Some countries use more than one criterion to differentiate the tax rates. For example, in Indonesia, differential rates are applied on products based on volume produced, type of cigarette and price level.2223

Mixed specific and ad valorem excise taxes

Some countries use mixed (or hybrid) excise tax structures and apply both specific and ad valorem taxes. Mixed systems usually combine a uniform specific tax which is relatively more impactful on cheaper brands and an ad valorem tax which has greater impact on more expensive price categories of brands.

Tobacco product excise applied by countries vary by region and income level. They also depend on policy objectives such as public health protection, revenue generation and the protection of domestic tobacco growers and/or manufacturers.24 The ad valorem component increases absolute price differences and consequently promotes use of cheaper brands – undermining public health objectives. However, the specific component reduces the relative price differences between cheap and expensive brands and contributes to minimizing the variability of prices.

A mixed system is more complex to implement and administer than a uniform specific tax structure, because it is based on the product value, which needs be determined at a specific point (distribution, retail, import) so more effort is required to calculate the payment. Manufacturers can easily underestimate their product prices, and thus ad valorem taxes, through legal or illegal accounting practices in order to avoid higher tax payments. Since tax revenues are based on both volumes and prices, revenues from a mixed tax structure are more difficult to forecast, less stable, and more dependent on industry pricing strategies than tax revenues under a uniform specific tax structure. However, the real value of the total tax will be less eroded over time by inflation than under a uniform specific tax structure.25

The key features of specific and ad valorem taxes are summarised and compared below:

| wdt_ID | Specific Excise Tax | Ad valorem Excise Tax |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stable and predictable revenue | Unstable and less predictable revenue stream |

| 2 | Easier to administer | Difficult to administer |

| 3 | Raise all product prices – reduce the gap between products | Leads to greater price differentials between products |

| 4 | Easier to determine the amount of tax | Difficult to determine the amount of tax |

| 5 | More effective in reducing tobacco use and raising revenue | Result in reduction in revenue and large price differentials between products - lead to consumer substitution |

| 6 | Promote higher quality products as industry gains more | Disincentive to product upgrades |

| 7 | Real value falls with inflation | Automatic adjustment for inflation |

According to WHO, the number of countries that rely solely on ad valorem taxes or apply no excise taxes at all has declined since 2008, as more countries are adopting specific or mixed systems.26 While those that have a mixed excise system in place, have increased the specific component of the tax structure relative to the ad valorem component.

The under-valuation of products is less likely in a mixed tax system than a pure ad valorem system. However, to further reduce to the risk of undervaluation, a minimum excise tax (MET) or minimum specific tax floor can be applied. The WHO FCTC Article 6 guidelines also recommend that Parties implement “specific OR mixed excise systems with a minimum specific tax floor, as these systems have considerable advantages over purely ad valorem systems”. The minimum tax functions as a specific duty and encourages a minimum price for each product on the market. This ensures relatively higher price levels for low and mid-priced products. The use of a minimum specific tax floor also ensures that a certain minimum excise tax will be collected on all brands, regardless of their retail selling price.20 The MET is designed to stop companies selling cigarettes so cheaply whilst providing revenue to government.27

Sales Taxes

These are widely levied consumption taxes, that are applied as a single rate on a broad range of goods and services, not just tobacco. ‘Value Added Tax’ (VAT) is applied in several countries including the UK and some other European countries. It is paid by the consumer at the point of sale and therefore reflected in the price paid when items are bought. They are collected by the retailer to pass on to the government. Unlike other taxes, this form of taxation is levied on the total value added at each stage of the production chain. An advantage of this tax is that it minimizes the amount of detailed information needed by tax authorities on the nature of the goods and services, as only the total value of sales needs to be recorded. Also, a sales tax does not affect the relative prices of products. Therefore, it is one of the best methods of revenue generation.21

Price sensitivity, elasticity and affordability

Consumers purchasing behaviours, or their willingness to buy a particular product or service, is largely dependent on the price, as well as their income. ‘Price sensitivity’ is the degree to which the price affects these decisions, and therefore demand for products.28 Price sensitivity varies with the kind of products and services available, the type of customers, uniqueness of the products or available substitutes, ease of switching, and wider market characteristics.29

Elasticity: Tobacco is a unique product due to its strong addiction potential and limited available substitutes in the market. As a result, the demand for tobacco products is relatively ‘inelastic’.303132 Price elasticity varies from country to country, and over time. The greater the absolute value of price elasticity for tobacco products, the higher will be the price sensitivity of demand and a resulting larger reduction in consumption.33

An increase in tax is expected to reduce demand (and therefore consumption), by lowering affordability and increasing price. However, the effect of tax and price increases on consumption can be offset by a growth in consumer income as the products will become more affordable. So, for taxation to be most effective, it is essential to account for the growth in income of the consumers when setting taxation rates.34

In LMICs, demand for tobacco products is more responsive to price. This has been found to be true for those with a lower level of education and/or those in low-income households. Tobacco use among youth is two to three times more responsive to price.35

Nevertheless, evidence suggests that affordability, more than just the price, is a better measure for determining tobacco demand and consumption. In countries that are growing fast (with increasing incomes) such as LMICs, affordability elasticity appears to be a better measure to determine the sensitivity of consumers to tax and price policy changes compared to high income countries (HICs) with more stable income trajectories.33

The tobacco industry’s pricing power

The tobacco industry enjoys significant pricing power owing to the oligopolistic nature of the tobacco markets: just four transnational tobacco companies – Philip Morris International (PMI), British American Tobacco (BAT, which includes Reynolds American Inc.), Japan Tobacco International (JTI, whose parent company is Japan Tobacco Group) and Imperial Brands – dominate the global market outside China.1836 The industry holds pricing power because tobacco is an addictive product generally with few substitutes available, so consumer demand remains relatively stable. (Where substitutes do exist, the market is often dominated by tobacco companies. See the page on newer nicotine and tobacco products.) This enables companies to increase prices almost at will. This in turn makes the manufacture of tobacco products extremely profitable, ensuring that profits rise even when volumes fall, which is true even with an unfavourable tax environment.19

Perhaps the most remarkable change in the tobacco industry in recent years is the increase in its pricing power: its ability to ensure that prices (and thus profits) increase more quickly than sales volumes fall.

Work by the Tobacco Control Research Group showed that an estimated 92% of revenue in the global tobacco market was generated from cigarettes (2010 data).37 Yet since 2000, growth in global cigarette sales has slowed to under 1% annually and, if China is excluded, global volumes have been falling.37 Despite this picture, industry profits continue to rise;19 the value of global cigarette sales has risen by 84% in the past decade, with increases in value even in markets experiencing major volume declines.37

Indeed, the profit margins in the tobacco sector far exceed those in other consumer staples industries.19 This profit and pricing power therefore gives tobacco companies options when it comes to responding to tax increases.

Industry pricing strategies

The success of any tobacco taxation policy largely depends on the extent to which the tax is passed onto the consumers in the form of higher prices. The industry targets different socioeconomic groups by employing highly efficient pricing strategies. Companies do this by creating hierarchical price categories for their products and organising them into different price segments, ranging from highly priced premium brands to mid-priced and low-priced economy cigarettes.38

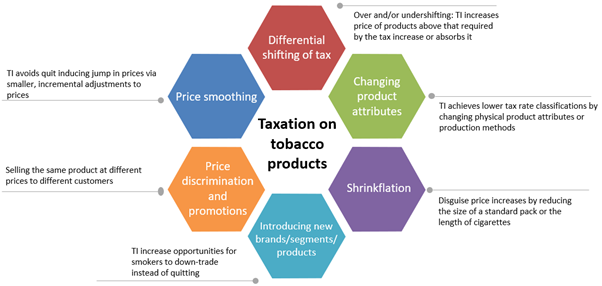

A review study carried out in 2021 by the Tobacco Control Research Group, found that the industry utilises six broad pricing strategies all over the world (both in HICs and LMICs) in order to undermine the effect of tobacco taxation.39

These are summarised in figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Tobacco Industry Pricing Strategies (TCRG original research)

For details and examples see Tobacco Industry Pricing Strategies

Price cap regulation

Price caps have been proposed as a way to reduce the impact of tobacco industry pricing policies.4041

Pricing as CSR

At times, tobacco companies have tried to portray their actions on price as part of being responsible corporate citizens. This is illustrated by BAT’s proposal for minimum pricing in New Zealand in 2010, which it framed as a way to protect children.

TobaccoTactics Resources

Tobacco Industry Pricing Strategies

Tobacco Industry Arguments Against Taxation

Relevant Links

The Price We Pay: Six Industry Pricing Strategies That Undermine Life-Saving Tobacco Taxes, STOP report, exposetobacco.org

Video in English, Urdu and Indonesian

Tobacconomics, University of Illinois (Chicago Institute for Health Research and Policy)

TCRG Research

How has the tobacco industry passed tax changes through to consumers in 12 sub-Saharan African countries? Z.D. Sheikh, J.R. Branston, K. Zee, A.B Gilmore, Tobacco Control Published Online First: 11 August 2023, doi: 10.1136/tc-2023-058054

Tobacco industry pricing strategies in response to excise tax policies: a systematic review, Z.D. Sheikh, J.R. Branston, A.B Gilmore, Tobacco Control, Published Online First: 09 August 2021, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056630

Industry profits continue to drive the tobacco epidemic: A new endgame for tobacco control?, R. Branston, Tobacco Prevention & Cessation, 2021;7(June):45, doi:10.18332/tpc/138232

Tobacco industry strategies undermine government tax policy: evidence from commercial data, R. Hiscock, J.R. Branston, A. McNeil et al, Tobacco Control 2018;27:488-497, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053891

Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: an analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials, A.B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control 2012;21:119-12, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050397

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to TCRG publications.