Latin America and Caribbean Region

This page was last edited on at

Background

Latin America and the Caribbean is composed of 33 countries, covering the territory from Mexico to Argentina, including the Caribbean islands.1 The region includes some of the countries with the highest population in the world, such as Mexico and Brazil. In 2018, the total population for the region was more than 641 million people, according to World Bank statistics.

Despite its economic growth and being a “biodiversity superpower”2, one of the main challenges faced by Latin America and the Caribbean remains the high levels of economic inequality.3 According to a report from the United Nations Development Programme, the richest 10% in the region have a higher share of salary than in any other region (37%) and the poorest 40% receive the smallest share (13%). This equates to one of the highest levels of inequality in the world.4

Smoking in the Latin American and Caribbean Region

Smoking prevalence in the region has been reduced in the last few decades as a result of the regional tobacco control efforts. The Pan-American Health Organization, which is the Americas regional office of the World Health Organization (WHO), estimates that “between 2007 and 2015, the prevalence of tobacco smoking dropped from 22.1% to 17.4%, a greater drop than that recorded globally”.5 This trend is expected to continue, with the region being the “only WHO region expected to achieve a 30% relative reduction in the prevalence of current tobacco use by 2025.”5

Despite the achievements on tobacco control, according to the Tobacco Atlas, “nearly 70 million smokers in Latin America are at risk of tobacco-related deaths and diseases”6. Bolivia and Chile have the highest smoking prevalence in the region, with 40% and 38.7%, respectively, followed by Cuba with 35.9%, Suriname with 26.2%, and Argentina with 22.5%. In contrast Ecuador (7.4%) and Panama (6.6%) have the lowest prevalence in the region. 7

A gender perspective on smoking in the region

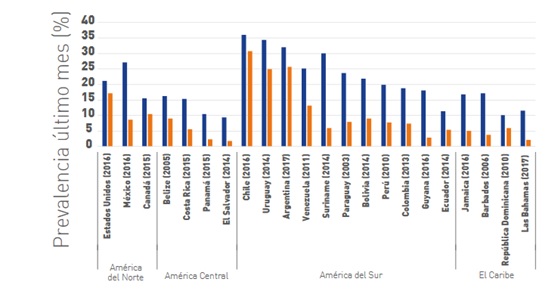

Men have a higher consumption rate compared to women, despite the tobacco industry’s long term efforts to target women in its marketing and advertising strategies.8 Even so, Latin America and the Caribbean are ranked second by the WHO, regarding higher rates of female tobacco consumption, following Europe.8 Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina have the highest rates of consumption among women (see the graph showing tobacco consumption in the general population by gender and country, with data in blue being for men and data in orange for women). 9

Figure 1: Smoking prevalence in LAC region. (Source: Organization of American States, smoking prevalence9)

Tobacco use among youth (10- to 15-year-olds) in the region

Jamaica has the highest rate in youth consumption in the region, with 28.7%, followed by Colombia with 22% and Chile with 19.7%. Brazil has the lowest rate of tobacco consumption amongst the youth, as a result of the efforts of the country to introduce tobacco control measures as advertising ban, health warnings, and flavouring ban 8.

Most countries in the region have a strict ban on the sale of tobacco products to minors, however, there is evidence to suggest tobacco use initiation starts between 10-13 years old, with those in Caribbean countries starting to smoke at a younger age on average than the rest of the region.8

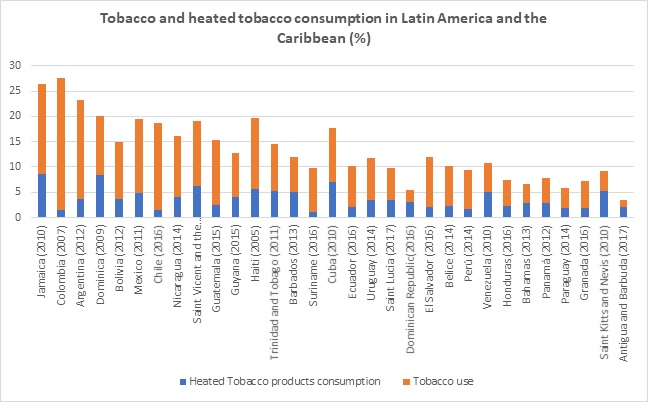

Figure 2: Tobacco and heated tobacco consumption in LAC region (Source: reproduction based on data from PAHO, 2007-2017)8

The consumption of newer nitcotine and tobacco products among the young population has increased in the region. However, conventional cigarette remains the highest consumed tobacco product. The following graph shows the consumption of tobacco products and next-generation products, by country. Jamaica also leads the consumption of next-generation products, followed by Dominica and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. 8

Tobacco production in the Latin American and Caribbean Region

Several countries in the region are major tobacco leaves growers and suppliers at a global level. Brazil has 75% of the regional tobacco production, followed by Argentina, Colombia, Guatemala, and Cuba representing 18.4% of the production collectively. However, the area of land dedicated to tobacco farming in the region has decreased from 668,890 hectares in 2006 to 556,372 hectares of land in 2014.10

Brazil is the second-largest tobacco-growing country in the world, after China.11 Tobacco farming in Latin America represents almost 16% of the global production. Moreover, the cultivated area in the region reaches 13.55% of the global land dedicated to tobacco farming worldwide 12 Central American countries such as Nicaragua, Cuba, Dominican Republic, and Honduras are the main global producers of cigars. 13

Who dominates the market?

The tobacco products that destroy so many people’s lives are the result of the activities of a number of companies around the world. The Tobacco Supply Chain Database enables tobacco control researchers and advocates to understand what the supply chain is, where it is located and who is involved. For more information, access the database here.

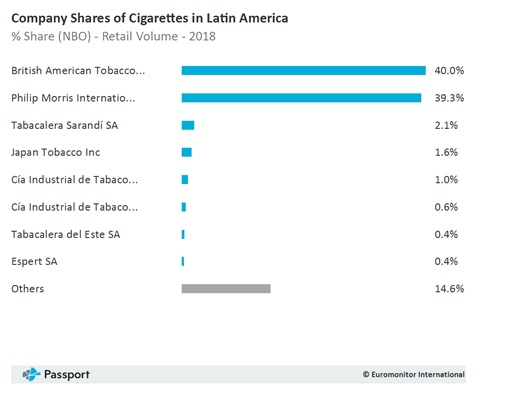

The tobacco market in Latin America and the Caribbean is dominated by Philip Morris International (PMI) and British American Tobacco (BAT). In the 1990s, BAT had 60% of the tobacco market, with PMI making up the majority of the remaining 40%, and some minor presence from Japan International Tobacco in Bolivia.14 However, in the late 2000s, Philip Morris started buying local manufacturers and tobacco brands. 15

Since 2015, British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International control the tobacco market in Latin America and the Caribbean, with BAT controlling 51.4% of the market. 16. In 2018, the company shares of cigarettes in Latin America showed BAT with 40.0% and PMI with a very close 39.5%, as shown in the following graph:

Figure 3: Company shares of cigarettes in Latin America (Source: Euromonitor 202017)

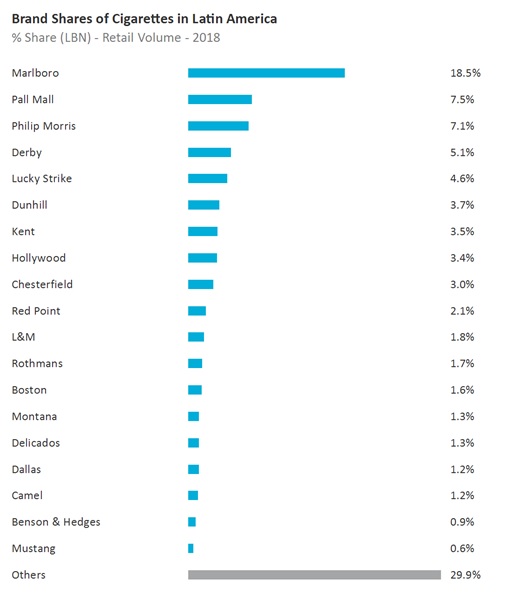

The most popular brand of cigarettes in the region in 2018 was Marlboro, by Philip Morris International, followed by Pall Mall, produced by the British American Tobacco. The following graph illustrates the brand shares of cigarettes in Latin America:

Figure 4: Brand shares of cigarettes in Latin America (Source: Euromonitor 202018)

| Country | Most sold cigarette brand | Brand owner |

| Argentina | Marlboro | Philip Morris International 19 |

| Bolivia | L & M | Philip Morris International 20 |

| Brazil | Marlboro | Philip Morris International 21 |

| Chile | Pall Mall | British American Tobacco 22 |

| Colombia | Marlboro | Philip Morris International 23 |

| Ecuador | Líder | Philip Morris International 24 |

| Mexico | Marlboro | Philip Morris International 25 |

| Peru | Hamilton | British American Tobacco 26 |

| Venezuela | Belmont | British American Tobacco, 27 |

Table 1. Countries with most sold cigarette brand owned by international and multinational companies, in the most populated countries of Latin America and the Caribbean

Links to the government

Latin America and the Caribbean has been a leader on tobacco control at the global level for decades. 28 29 The region has a world-renowned reputation for its tobacco control efforts, including the design and implementation of effective evidence-based policies. As a consequence, the tobacco industry has attempted numerous times to undermine those efforts. As described by regional tobacco control experts: “The tobacco industry, with enormous resources and possibilities, is on high alert and giving a fierce and intelligent fight. What is visible, at least in the Americas Region, is that they continue to rely on the old tactics (albeit more aggressively): lobbying directly, especially in finance ministries and also at higher levels of government, to oppose tobacco tax increases, advertising bans or neutral packaging.”8

Latin American and Caribbean government representatives have long recognised the pressures they are under from the tobacco industry. An expert committee from the Pan-American Health Organization was convened in the year 2000 to evaluate the industry interference in the region. 30

In 2010, PAHO convened a meeting for Ministers of Health to discuss the issue. Delegates pledged to counteract efforts by the tobacco industry or its allies.30 After this meeting, the Executive Council of PAHO met in October 2010, to keep discussing the industry interference through lobbying of decision-makers, threatening litigation and influencing the political discussion around tobacco regulation in the region.

Aznar lobbying for PMI in Chile and Peru

A tactic that the industry often uses in the region is hiring high-level lobbyists to influence government officials. Such is the case of José María Aznar, the former Spanish Prime Minister and President.31 Since 2018, it has been widely reported by the international media that Aznar has taken a position as a lobbyist for PMI in Latin America. 323334

Chile

According to public records from the Government of Chile, Aznar met with the Chilean Minister of Finance, Felipe Larrain Bascuñan, and the Chief of Staff of the Ministry of Finance, Francisco Matte Risopatrón, on 8 May 2018.35 The next day, on 9 May 2018, as stated in the public records, Chilean Minister Felipe Larrain Bascuñan met for an hour with several lobbyists from different multinational corporations, including two lobbyists for PMI.36

Peru

In January 2019, the Congress of the Republic of Peru, began discussions on stricter tobacco product regulations, including a ban on tobacco advertising.37 At the same time, a group of congress representatives from Fuerza Popular, one of the main right-wing parties of Peru, submitted the 3833 bills 38 to replace the current tobacco control law 27805 with less restrictive regulations. These proposed amendments would allow the introduction of e-cigarettes (also known as electronic delivery systems, or ENDS) in Peru.39

Several newspapers and media outlets reported that Aznar travelled to Peru, in February 2019 on a similar mission to the one in Chile, lobbying for the tobacco industry.40 41 Allegedly, Aznar made an appointment to meet with the Minister of Health but did not attend this meeting in the end. 41

Montepaz lobbies for change to the law in Uruguay

On 2 September 2022, President Luis Lacalle Pou signed a decree to modify Uruguay’s plain packaging law. It would have reintroduced soft cigarette packs; removed the requirements for the inside of the pack to be plain white in colour and for packs to be lined with metallic foil; and abolished the prohibition on logos or branding on the cigarettes themselves.42 Lacalle Pou argued the reforms were necessary to fight illicit trade, and said that the decree was a response to a request from Montepaz, Uruguay’s largest tobacco company:43

“Is this to benefit the company Montepaz? No, it was a chewing gum factory who asked for it!” he said sarcastically, adding: “Who manufactures cigarettes in Uruguay? Montepaz. Who was it who asked the Ministry of Industry for this change? Montepaz. Now, if anyone believes that we just bow to pressure, they don’t know us, that’s disrespectful.”44

In February 2020, following publication of the 2019 election campaign finances by the Uruguayan Electoral Court, the newspaper El Observador reported that Montepaz had donated around $13,000 to the campaign of Lacalle Pou and his running mate Beatriz Argimón.45 In local currency, the amount reported is 552,180 pesos, as per the published document.46 In September 2022, following the decision to modify the plain packaging law, The Tobacco Epidemic Research Centre (CIET), a Uruguayan NGO, highlighted that political contributions by tobacco companies are illegal under both the WHO FCTC and Uruguayan law.47

It also emerged that in April 2022, Montepaz had hosted Nicolás Martinelli, then an advisor to President Lacalle Pou, at company headquarters. Martinelli published photos of the visit on his Instagram, alongside comments publicising Montepaz’s creation of employment.48

In October 2022, responding to an appeal by the Uruguayan Tobacco Control Society, the courts suspended the decree, on the grounds that it violated the right of children and adolescents to protection from inducement to tobacco use.49

Roadmap to tobacco control

Latin America has had an important role in the negotiations on global tobacco control policies. An example is the WHO FCTC negotiations and diplomatic processes, where the region was represented by Brazil. The Brazilian ambassadors were chosen to be the two first consecutive chairs of the intergovernmental negotiations. Chile also stood out, by later becoming chair of the negotiations towards the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. 50 Latin American leadership on tobacco control has also been shown by the important roles carried out by Latin American women in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control Secretariat. Dr. Vera Luiza da Costa e Silva from Brazil was head of the WHO FCTC Secretariat for six years (2014-2020). Additionally, the former PAHO Tobacco control diplomat from Uruguay, Dr Adriana Blanco, was appointed in 2019 as the new head of the Secretariat until 2024. 51

In the road to achieving tobacco control in the region, civil society has also had an important role and continues to do so. Beatriz Champagne, Latin-American tobacco control expert, argues that “Civil society has been the engine that has permitted many of the accomplishments seen in tobacco control in Latin America and the Caribbean. However, as civil society efforts frequently involve work behind the scenes, results may merge with those of other institutions and might be not recognized”52

Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and MPOWER in Latin America and the Caribbean

Most countries in the region have signed and ratified the WHO FCTC, as the following map illustrates. The exceptions are Argentina, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The most recent countries to ratify the Convention from the region are El Salvador and St. Vincent and the Grenadines, in 2014 and 2011 respectively. 53

Figure 5: FCTC parties in Latin America and Caribbean region. (Source: TobaccoTactics own production)

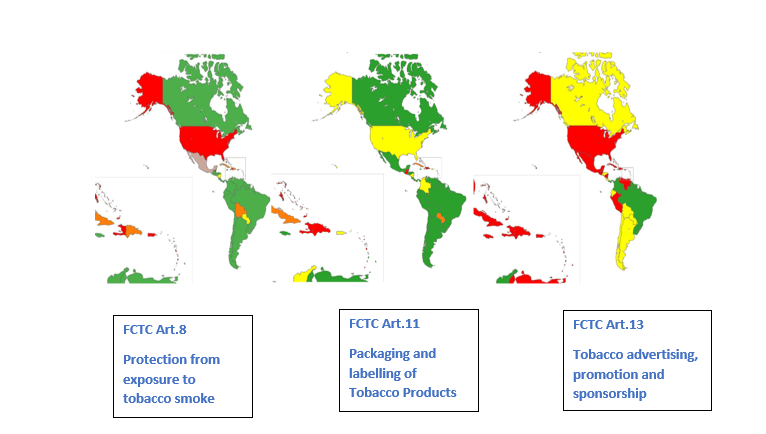

In terms of implementation of the WHO FCTC and the MPOWER program of six policies designed to reduce the global tobacco epidemic, the following progress has been achieved by 2019. Out of the 19 signatories’ countries that have provided data to PAHO:

- 13 countries are implementing and complying with article 8 on protection from exposure to tobacco smoke 54

- 13 countries are implementing and complying with article 11 on health communication and packaging regulations for tobacco products. 54

- 13 countries are implementing policies recommended by WHO in MPOWER on warning people about the dangers of tobacco. 54

- seven countries (Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Uruguay) are implementing recommendations by WHO in MPOWER on monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies54

- Only four countries (Brazil, Colombia, Panama, and Uruguay) are implementing and complying with article 13 on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship. 54

- Only four countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Colombia) are implementing and complying with a 75% or higher tax to tobacco products. 54

- Only four countries (Brazil, Colombia, Panama, and Uruguay) are implementing recommendations by WHO in MPOWER on enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship 54

- Only three countries (Brazil, El Salvador, and Mexico) are implementing recommendations by WHO in MPOWER on offering help to quit tobacco use54

Even though these results might not be achieving the goals set by the region to reduce the global tobacco epidemic, the scenario has improved remarkably in the last 20 years, especially with implantation of the FCTC. The difference between the implementation levels in the region between 1999 and 2019, is substantial.

The map illustrates the status of tobacco control policies implementation in Latin American and Caribbean countries in 2019, from right to left in the map, on Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke (art.8), Packaging and labelling of Tobacco Products (art. 11) and ban of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship (art.13). In red, the countries that have not implemented the different articles and in yellow and green the countries that are on the path to implementation.

Figure 6: Adherence to WHO FCTC articles in the Americas. (Source: reproduction from data provided by Adriana Blanco, PAHO, 201954)

As can be observed, the scenario has improved drastically despite the tobacco industry efforts to prevent regulations to pass in the region. Some successful cases of preventing tobacco industry to interference in the discussions and passing of tobacco regulations are:

- the case of Panama in 2008, which was the first Latin American country to instate advertising, promotion and sponsorship ban, complying with the WHO FCTC recommendations. BAT and PMI tried in three different legal stances, to counter these effective measures. The Panamanian Supreme Court ruled in favour on the Ministry of Health and the health prevention measures, supporting the country´s efforts to end the tobacco use epidemic55

- the case of Guatemala in 2008, when the country was able to prevent the interference of the tobacco industry during the passing of the national law towards the implementation of 100% smoke-free environments. As reported by the InterAmerican Heart Foundation, “The Supreme Court dismissed the public action for unconstitutionality filed by the tobacco industry through the Chamber of Commerce with the objective of preventing the adoption of such measure” 56

- the case of Honduras in 2010, where during the debates towards the Special Tobacco Control Act 2010, the National Congress decided not to allow the participation of tobacco industry representatives. The Congress acted, despite the persistent request of the Honduran Council of Private Corporations and other congressional representatives. Honduran law explicitly prohibits “all interference from commercial or other vested interests of the tobacco industry”.56

- the case of Peru in 2010, during discussion of the tobacco control bill at the parliamentary commissions, where the participation of representatives of the tobacco industry was not allowed. The industry interference was prevented mainly thanks to an active engagement of the tobacco control civil society. 56

- the case of Brazil in 2019, where the Office of the Attorney-General of Brazil filed a lawsuit at the Federal Court of Rio Grande do Sul against the big tobacco corporations in Brazil and their parent companies abroad, “to seek recovery of healthcare costs related to the treatment of tobacco-induced diseases. The claim covers costs generated in the Brazilian healthcare system for the treatment of patients suffering from 26 diseases linked to the consumption of tobacco products and exposure to tobacco smoke, and foresees proportional compensation for future spending, and collective moral damages, as a consequence of the tobacco public health burden.57

Industry interference

Challenging legislation

The tobacco industry has a history of challenging legislation, tobacco control programmes and regulation that affects its sales. It does through this direct lobbying, using third parties and legal threats.

Research conducted by PAHO in the region58 shows that one of the key tactics that the industry often uses is to offer “self-regulation” deals, that involve the drafting of their regulations for the Latin American and Caribbean countries. According to PAHO: “The industry’s legislative proposals, like its voluntary codes, typically contain minor concessions that the industry believes will not significantly impact tobacco sales, and are intended solely to build corporate image and, most importantly, block or at least delay meaningful regulation.”58

An historical record of this tactic is illustrated in a quote obtained from the leaked industry documents about Nicaragua in 1992, when the Central American country was trying to pass tobacco regulations. This message came from TANIC, one of BAT´s subsidiaries in Nicaragua: “Experience elsewhere has shown that it is desirable to be ahead of the game and try to contain legislation rather than repair damage after the event. … TANIC must be in a position to influence … legislation to protect or promote its interests.”58

In the region, several cases serve as example of how the industry seeks to undermine public health efforts via this tactic:

Tobacco tax raise in Colombia

In 2015, the price of cigarettes in Colombia was one of the lowest in the region, at approximately US$2 per 20 cigarette pack. According to data from the Ministry of Health of Colombia, “The direct cost to the Colombian health system attributable to smoking for the same year was over US$ 1 billion equivalent to 0.6% of the Gross Domestic Product.” 59. Colombia, Party to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, decided to move towards the implementation of the WHO´s recommendation of at least 75% tax of retail price of tobacco products.60 Colombia´s government decided to increase progressively, starting from their baseline of 49.4%.61

Implementation of the 2016 tobacco tax reform placed Colombia as a regional leader in tobacco control. In the first year of implementation it helped reduce the number of smokers by close to 400,000 while increasing tobacco tax revenues by 46%.62With more than 32,000 people dying from the tobacco-caused disease in Colombia every year63 it is vital to protect and sustain the tax. Philip Morris International, the leading seller of cigarettes in Colombia, has a long history of aggressive opposition to tobacco control measures. For more information, see the Tobacco Tactics web page on Philip Morris International.

In 2019 PMI campaigned to intimidate policymakers, infiltrate the policy process and undermine Colombian legislation. For example, PMI blamed factory closures on tobacco control measures,64 co-opted anti-smuggling programs,65 and attempted to discredit the success of the tobacco tax at a congressional hearing.66 Its dubious claims linking increased tobacco tax to increased illicit trade purposefully ignored the fiscal and public health benefits gained, as supported by independent investigations in Colombia 6768and by the World Bank 69

Interference in newer products regulations in Chile

Electronic cigarette consumption in Chile has grown from 3.6% in 2014 to 6.5% in 2016 amongst those aged 12-65. 70 The highest prevalence of electronic cigarette consumption has been consistently observed in younger age groups (15-24 years) particularly in area around the capital Santiago where the consumption of electronic cigarettes among those aged 13-15 years was 12.1% in 2016.71

The Institute of Public Health regulates e-cigarettes as a pharmacological product. The National Agency of Medicines, as the governing body of the certification of medicines in Chile, authorized some of these products to be marketed as pharmaceutical products, when it could have been regulated by existing regulations on tobacco.72 In September 2019, a new bill was sent to Parliament proposing to regulate e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products as tobacco products. Under this proposed bill, these newer would be regulated by the tobacco law enacted in 2013, resulting in a ban on advertising and promotion, the sale to minors, and smoking or vaping in enclosed spaces and they would need to include health warnings like conventional cigarettes. 73 However, the discussions around this bill were delayed due to the political complications that the country faced at the end of 2019.

Standardised packaging: Uruguay vs Philip Morris

Uruguay has some of the most progressive tobacco control policies in the world. In October 2017, Uruguayan President Tabare Vázquez announced that his government would introduce plain packaging legislation, becoming the seventh country to do so, following Australia, UK, Ireland, France, Norway, and Hungary.7475

In February 2010, PMI (represented by law firm LALIVE) challenged Uruguay using the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes. It sought damages under the Switzerland-Uruguay Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) for tobacco control regulations.7677

The company claimed that Uruguay’s regulatory measures violated the investment protection agreement signed in 1991 between Uruguay and Switzerland, where PMI is headquartered.78 PMI claimed that the case was about trademark protection and called the design of some of the six health warning messages “repulsive and shocking”. It said: “We do not oppose the use of graphic health warnings but believe that images should accurately depict the health effects of smoking… We have a powerful case, and in the absence of any change to these excessive regulations we will continue with our claim.” 79

In July 2016 The World Bank’s Court dismissed all claims that Uruguay had breached the 1991 BIT, stating that Uruguay had “the right to continue its anti-cigarette campaign”, and ordered the company to reimburse the state’s legal expenses.80

Uruguay is not the only country that has been taken to court by the tobacco industry over tobacco control measures. For an overview of some of the tobacco industry’s legal challenges across the world, go to Tobacco Tactics page on Legal Claims.

Influencing science

The tobacco industry has a long history of influencing the scientific debate on smoking and health. Tens of thousands of internal industry documents, released through litigation, reveal that the industry knew for decades that its products caused cancer and were highly addictive and yet it refused to acknowledge this publicly. The tobacco industry continues to influence the science around smoking and tobacco in an effort to frustrate regulation and protect profits.

Latin America and the Caribbean have not been exempted from the influence of these tobacco industry tactics. Tobacco control researchers from the region have been pressured by the tobacco industry not to publish their results and to alter the content of their research findings. The Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO) published a report on tobacco industry influencing science in 2002, going over thousands of leaked documents from the tobacco industry, mainly from British American Tobacco and Philip Morris International. The report revealed that the tobacco industry had hired scientists across the region seeking to distort scientific findings linking passive exposure to cigarette smoke with serious disease. Furthermore, the tobacco industry failed to disclose any connection or involvement with these scientists and researchers. 81

One historical example was the Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) consultancy program, described as “the core industry strategy to undermine efforts to reduce second-hand exposure, was jointly financed by PM and British American Tobacco, and coordinated by the Washington, D.C. law firm of Covington and Burling.” 58 This program began as a global strategy in 1987, hiring experts from other countries to work in Latin America. Later, in 1991, Latin American experts from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala and Venezuela, were hired for this program.58

Information uncovered from the leaked documents analysed by PAHO in this report had quotes from the industry said:

“Unlike many other regional ETS consultant programs sponsored by the industry, the Latin project was initiated in anticipation, rather than in reaction to, the full-force arrival of the ETS issue to Central and South America… Critical to the success of the Latin Project is the generation and promotion of solid scientific data not only concerning ETS specifically but also concerning the full range of potential indoor and outdoor air contaminants. This approach encourages government agencies and media in Central and South America both to resist pressure from anti-smoking groups and to assign ETS its proper place among the many potential indoor and outdoor air contaminants found in these regions.”58

Further examples are the PMI Impact funded projects in Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil, which, as describe in the PMI website, seek to develop models on illicit trade in the triple-border area, as well as in Central American countries as Honduras and El Salvador. 82

The industry has always pushed for its funded projects to be perceived as “independent”. The leaked documents uncovered in PAHO´s report show that fabricating independency of these research centres is part of the industry´s strategies. A quote from a BAT executive in Costa Rica, regarding the collaboration program between BAT and PMI to influence science in the region, says : “I cannot stress strongly enough the absolute necessity for the industry to have no direct contact with these scientists [the consultants] that are part of the program. … If one scientist in the group is perceived by anyone to be associated with the industry, then we run the risk, by association, of this happening for the rest of the group and the whole exercise will become pointless. All contact, as previously explained, must be carried out through Covington & Burling.”58

The region still faces many challenges in identifying industry-funded data, uncovering the academic and scientific organizations collaborating with the industry and countering the pressure on tobacco control researchers aiming at publishing evidence-based papers and reports.

Political contributions to political parties in Latin America

Another tactic that the tobacco industry uses in Latin America and the Caribbean, is lobbying decision-makers through financial political contributions to political parties. PMI has been making these financial political contributions to political parties in Latin America for years. 83

Since 2010, Philip Morris International official records show that this tobacco company has contributed to:

- Dominican Republic political parties in 2016: US$ 66,803 in 2016 84

- El Salvador political parties in 2015: US$ 10,000 85

- Brazil political parties in 2014: US$ 520,059 86

- El Salvador political parties in 2012: US$ 9,000 87

- Dominican Republic parties in 2011: US$ 4,887 88

- Brazil political parties in 2010: US$ 567,860 89

British American Tobacco does not declare political contributions to political parties in the region, however, it does contribute extensively in the United States and Europe. 90

The challenges ahead for the region are directly influenced by the constant pressure that the governments experience by the tobacco industry and its tactics.

Tobacco Tactics Resources

References

Categories

- British American Tobacco

- Challenging Legislation

- E-cigarettes

- Farming

- Influencing Science

- Japan Tobacco International

- Latin America and Caribbean

- Legal Strategy

- Lobbying Decision Makers

- Lobbyists and PR People

- Philip Morris International

- Politicians

- Price and Tax

- Region profiles

- Revolving Door

- Supply Chain

- Tobacco Advertising, Promotion, and Sponsorship