PMI’s IQOS: Use, “Switching” and “Quitting”

This page was last edited on at

Key points

- Philip Morris International (PMI) is increasingly moving into the ‘cessation space’.

- The US Food and Drug Administration denied PMI “reduced risk” status for its heated tobacco product IQOS. Nevertheless, PMI continues to push it as a cessation product, including in countries where it is currently banned.

- PMI uses misleading terminology when talking about IQOS use and “quitting”, and conflates its e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products (HTP), leading to confusion among the public, and potentially governments.

- PMI’s data for global IQOS use, used to promote the HTP and present it as a successful product around the world, are based in part on commercial data which is not publicly available and is skewed by data from Japan where e-cigarettes are banned.

- PMI’s ‘switching’ estimates are short term and downplay dual use of IQOS with cigarettes and the potential for initiation by non-smokers, including youth.

- There is very little evidence that IQOS is effective as a quit tool at the individual level or population level.

- Not all governments are prepared to accept IQOS as a cessation tool.

Background

Philip Morris International (PMI) has stated that it has a vision of a “smoke-free” future and that it intends to move its business away from combustible tobacco products entirely.12 PMI envisages itself and its heated tobacco product (HTP), IQOS, as central in this vision. However, independent evidence does not support many of PMI’s claims about its product, including its claims about risk reduction and its effectiveness in helping people stop smoking. PMI’s commercial goal is not to stop people using tobacco altogether, but to ensure they continue to buy its products, including IQOS, and to increase the numbers of people doing so.3

PMI uses its own research and market data to produce estimates about users, IQOS usage, and the use of other tobacco products. While research on IQOS use is available on the PMI Science website and in some external publications (see below), PMI’s methodology for calculating its global estimates of IQOS use is not transparent. While there has been some independent research on the prevalence of HTP use (including IQOS), as of January 2023, PMI’s estimates for the total numbers of IQOS users globally were yet to be independently verified.

The Philip Morris company has a history of claiming that it promotes cessation.4 It even created its own, limited cessation programme called “QuitAssist”, launched in 2004 before PMI separated from parent company Altria.45 This was not proven to be effective, but gave the company opportunities to engage with public health and government.4 (See also the page on Duke University and its connections to QuitAssist)

This page describes some of PMI’s more recent attempts to enter the ‘cessation space’ with IQOS. It then looks at relevant PMI statements from media interviews, press releases and industry publications, and the evidence it uses to support its claims, including that submitted to the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It summarises the independent, peer reviewed academic research relating to the use of IQOS, including prevalence, dual and poly use, and youth initiation. Finally, it describes the reaction from the governments of Australia, New Zealand and Mexico in 2020, in response to PMI’s attempts to introduce IQOS to their countries and frame them as cessation products.

What is cessation?

Use of the terms “cessation” and “quitting” varies, even within public health, and can be conceptualised in different ways, for example:

- Quitting/cessation of smoked tobacco products

- Quitting/cessation of any tobacco product

- Quitting/cessation of any nicotine product

Products containing, or derived from, tobacco do not necessarily fall neatly into these categories, as definitions vary globally for the purposes of regulation and cessation.

The tobacco industry is able to take advantage of this diversity of opinion,6 and different attitudes towards harm reduction more broadly, to further its own commercial interests. For example, HTP manufacturers have gone to great lengths to frame HTPs as “smokefree” in order for potential consumers, governments and regulators to view them differently from combustible tobacco products, like cigarettes.37 However, HTPs contain tobacco leaf and are therefore tobacco products.

PMI attempts to re-enter the ‘cessation space’ with IQOS

As governments increasingly struggle to fund their public health services and set up new smoking cessation (or ‘quit’) programmes, new opportunities have emerged for the tobacco industry to present itself as a solution to the problem it has created: getting consumers hooked on cigarettes, a deadly and addictive product.891011

Proposed £1 billion fund for UK stop-smoking services

In February 2020, an investigation by The Guardian newspaper and Channel 4 TV’s Dispatches programme exposed PMI’s attempt to fund and run cessation services in the UK, in exchange for being able to promote IQOS.12 Leaked documents showed that the company planned to create a GB£1 billion “tobacco transition fund” to be spent by UK health authorities, with GB£15 million to go to Public Health England to “facilitate switching”.12 In exchange, PMI expected the lifting of restrictions on the advertising and marketing of IQOS and e-cigarettes. The Guardian reported that PMI encouraged a UK Member of Parliament, Kevin Barron, to present an (unsuccessful) bill proposing this in parliament in October 2018.12

Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) described this move by PMI as “completely unacceptable” and expressed concerns that the company’s ability to recruit a previously anti-tobacco MP to further its business interests was a sign of increasing normalisation of the industry in the UK.1213 Philip Morris’ statement to The Guardian indicated the range of its lobbying in the UK, in its attempt to co-opt existing cessation campaigns and undermine the ‘polluter pays’ principle proposed by ASH:13

“We have made this point time and time again to MPs, civil servants, local councillors, journalists and the broader public. What this story really shows is that Philip Morris has been consistent in its efforts to make smoke-free 2030 a reality.”12

Offered free IQOS to cessation services in New Zealand

In August 2019, a Radio New Zealand (RNZ) investigation reported that health officials had been lobbied by PMI to have IQOS included in public cessation programmes.1415 The company proposed supplying free IQOS devices in exchange for “community-based trials, data collection and monitoring”.14 It is not known if PMI were expecting the programmes to use IQOS exclusively, or alongside other evidence-based cessation tools. RNZ also reported that PMI had approached an advocacy group working with people on low incomes and had sold IQOS to Maori groups at half price.14 New Zealand’s Director General of Health, Ashley Bloomfield, said that PMI was:

“doing its best on all fronts to … legitimise both its product and its role in being part of smoking cessation initiatives around the country.”14

Bloomfield instructed health officials to reject PMI’s approaches and reminded them of their obligation under FCTC article 5.3.1416

Funding cessation programmes through Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

PMI set up, and is the sole funder of, the Foundation for A Smoke Free World (FSFW). FSFW funds a number of cessation-related projects globally and, in 2020, appeared to be expanding this area of work. The Centre for Health Research and Education (CHRE), a private company run by an ex-employee of British American Tobacco (BAT) and a UK doctor, received grants from FSFW for cessation work in the UK, and to fund the scoping of work in India.17

In July 2020, FSFW published a country report on India.18 This covered research on cessation in India, mentioning nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and “cessation medications”, and perceived gaps in provision, including the training of health care professionals and the establishment of tobacco cessation centres. In a section titled “Policies Prohibiting Tobacco and Harm Reduction Products in India”, it referred to India’s ban on e-cigarettes and other products and stated that “There is a growing demand for reduced-risk products globally, as well as evidence on e-cigarettes as a potential cessation tool, and it is important to consider the implications of this ban”.18 However, there appeared to be no further detail, or policy recommendations relating to cessation.

The Centre for Research Excellence: Indigenous Sovereignty and Smoking (COREISS) is a private company which presents itself as an independent scientific organisation whose stated goal is reducing tobacco-related harms among indigenous peoples. COREISS was funded by FSFW to “build a global center for smoking cessation and harm reduction in indigenous people” in New Zealand.17

For more information see the CHRE and COREISS pages. Details of other FSFW grants can be found on the FSFW grantees page. FSFW also funds a number of third-party organisations which campaign for a greater role, and fewer restrictions, on newer nicotine and tobacco products. See for example the International Network of Nicotine Consumer Organisations (INNCO), Knowledge-Action-Change (K-A-C) and Pakistan Alliance for Nicotine and Tobacco Harm Reduction (PANTHR). PMI also directly funds Factasia.

The risks of using IQOS vs quitting

PMI portrays IQOS as a “reduced risk” product.3 In July 2020, the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted PMI a “modified exposure” order but denied a “reduced risk” order, acknowledging that while IQOS reduces exposure to some potentially harmful chemicals it has not been shown to reduce the harm or risks of tobacco-related diseases.19

In July 2020, the WHO stated that there was a large gap in knowledge on HTPs, as they have not been on the market long enough to gather data on their health effects and broader impact.

“Conclusions cannot yet be drawn about their potential to attract new, young tobacco users (gateway effect), or the interaction in dual use with other conventional tobacco products and e-cigarettes”.20

The Tobacco Control Research Group (TCRG) published a STOP briefing, and British Medical Journal editorial pointing out the potential for the misrepresentation of the FDA’s decision outside the US and advising that smokers trying to quit should use evidence-based methods, and only use HTPs “as a last resort”.2122

Creating confusion around science is a long-standing tactic of the tobacco industry. For more information see Influencing Science

Redefining “quitting” as “switching”

Although PMI uses the word “quitting” in its public-facing media statements and interviews, it frames the concept in terms of “switching”, “converting”, or “making the change” to IQOS, rather than quitting tobacco use entirely.2324 In its September 2020 “Scientific Update”, the word “quitting” appears once, compared to 20 uses of “switch”25 (“cessation” is only used in a summary of an academic study on e-cigarettes).

PMI has denied that the name “IQOS” stands for “I Quit Ordinary Smoking”.2627 However, Stanford University research on PMI’s IQOS marketing campaigns noted that even the use of the letter Q in the brand name reinforces the sense that the product is designed for ‘quitting’.28

The WHO points out that consumers and regulators are likely to confuse or conflate the terms “switch” and “quit”, blurring the line between the two concepts, and helping the tobacco industry to position their HTPs as cessation aids (as well as arguing that they should be exempted from smoke-free regulation).8

PMI’s estimates of the numbers of IQOS users are widely reported in media coverage around the world, and there is evidence that they are also being used by PMI to lobby governments to encourage governments to open their markets to IQOS.21

For more information see PMI’s promotion of IQOS using FDA MRTP order

Conflating HTPs and E-cigarettes

PMI has also appeared to conflate HTPs and e-cigarettes (also known as electronic nicotine delivery systems, or ENDS) in its marketing. This has the potential to sow further confusion.22 For example, in its ‘Hold My Light’ campaign, it said that “similar to most e-cigarettes” HTPs produce a “a nicotine-containing vapour with much lower amounts of harmful chemicals than found in cigarette smoke”.3 This was described by Bath researchers as an attempt “to piggyback HTPs onto the relative acceptability of e-cigarettes as a form of harm reduction in some countries that permit their sale”.3

PMI had an e-cigarette called IQOS Mesh on the market in the UK until April 2020, when it appeared to have been withdrawn. PMI presented IQOS Mesh, now apparently rebranded as IQOS VEEV, as a product suitable for “e-vapor users, adult smokers considering the e-vapor category and dual users of e-vapor and heated tobacco products”. 2930 Consumers are likely to find this confusing, given the similar name to PMI’s HTP.

Researchers found that in New Zealand PMI conflated heated tobacco products (HTPs) with ENDS in its marketing material, with both products sold in dedicated stores called “IQ Vape”.31 Price promotions for IQOS products were “explicitly encouraging consumers to dual use an HTP with ENDS”.31 Changes identified in PMI’s marketing principles in 2019 indicated that IQOS HTPs can be promoted to users of other nicotine products, not just cigarette smokers, which could include former smokers using nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).31 The researchers also identified conflation in PMI’s descriptions of risk profiles, noting that, while PMI’s press releases argue that the public lacks clear information on products and risk:

“by conflating HTPs with ENDS, the company risks doing the very thing it says it opposes: propagating confusion and misinformation amongst consumers.”31

IQ Vape has also been registered by PMI as a trademark in New Zealand.323334 Europe,35 and elsewhere.36

While there have been randomised controlled trials (RCTs) using e-cigarettes to aid cessation,37 at the time of publication there had been no RCTs testing the use of IQOS as a cessation aid.

PMI may also be conflating its products through business relationships. In Ireland, PMI joined the e-cigarette trade association Vape Business Ireland.38 In 2021, PMI’s membership was listed on VBI’s website as IQOS, rather than the e-cigarettes brand Veev.39 See also the page on UK retailer VPZ, which has a close financial relationship with Philip Morris Ltd, and markets IOQS HTPs in its stores as well as e-cigarettes.

- For more information on Mesh and VEEV and Vape Business Ireland, see E-cigarettes: Philip Morris International.

IQOS “Use”, “Switching” and “Conversion” – What Does PMI Mean?

The term IQOS “user” was used frequently in PMI annual reports and presentations to shareholders from 2018 onwards and refers to the “IQOS user base” when reporting its financial results.40

PMI defines an IQOS “user” as an adult who has used the product for at least 5% of their total tobacco consumption for a period of 7 days.41 A “predominant user” would need to have used IQOS for at least 70% of their consumption and a “converted user” for 95%. It also has a broad category for those who use IQOS for between 5% and 70% of their consumption, which it calls a “situational user”.41

Conversion rates are a commonly used metric in tobacco research, referring to the rate of transfer from first use of a cigarette (commonly youth use) to regular, daily smoking.42 PMI’s definitions do not appear to be based on any classifications commonly used in prevalence and cessation surveys, and it does not explain its rationale for how it developed its percentage bands. While the bands may serve to categorise users of IQOS, they do not predict cessation success or equate to the reduction of harm.

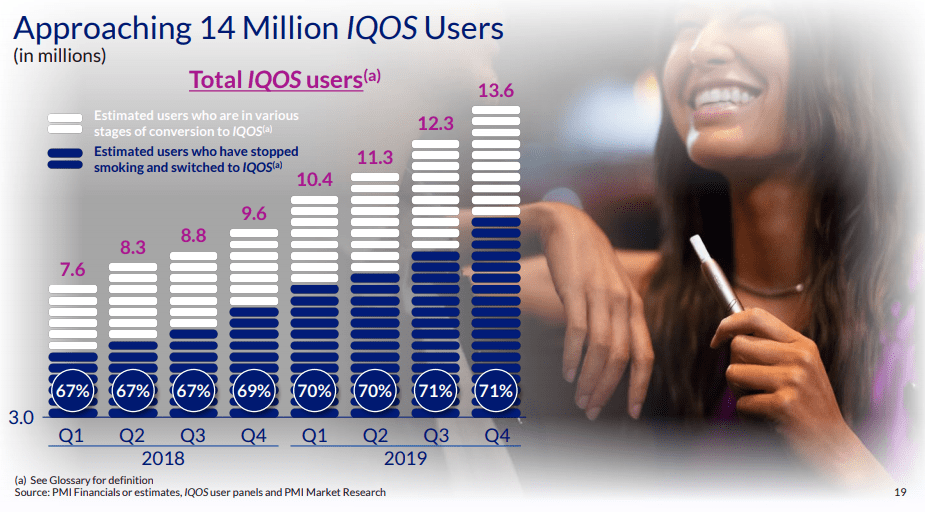

In February 2020, PMI stated that 14 million people were using IQOS. According to PMI, 10 million IQOS users (71% of the total) had stopped smoking and “switched” to IQOS, and an estimated 4 million were “in various stages of conversion” (i.e. still smoking cigarettes).43PMI regularly updates these figures in its public statements. In September 2020, CEO Andre Calantzopoulos gave a figure of 11.2 million as having ‘switched’ to IQOS.44 By the end of 2021, PMI stated that this had risen to 21.2 million.45

PMI states that its “aspiration” is for the number of smokers switching to IQOS to exceed 40 million by 2025.46

What are its estimates based on?

It is not clear how PMI calculates its user estimates. In its presentations and corporate reports, it states that they are based on a combination of “PMI financials or estimates, IQOS user panels and PMI market research” (see Image 1 below).47Information on IQOS sales and revenue from IQOS (but not profit) is reported in company statements, but PMI does not share the raw data from its user panels or market research.

Image 1: PMI’s estimates of IQOS users 2018- 2019 (Source: PMI, 2019 Fourth Quarter and Full Year Results presentation, 6 February 2020)

In 2019, PMI said that it would conduct a series of annual surveys to estimate the prevalence and use patterns of IQOS and other nicotine products in Germany, Italy and part of the UK.48 PMI stated that “the results of the first year data analysis are expected to be available by June 2019”. As of January 2023, these results did not appear to be publicly available.

The “PMI Science” website presents some findings relating to the use of IQOS based on surveys conducted in Japan between 2016 and 2018.4950

The problem with “conversion”

PMI stated in a 2018 presentation to shareholders that “High full conversion rates for an RRP [Reduced Risk Product] product [sic] are of fundamental importance” to consumers, the company and regulators as it “underscores a higher potential to meaningfully improve public health, as [IQOS] has a demonstrated ability to switch current smokers to proven better alternatives than cigarettes”.51

However, PMI’s estimates for those who have “converted” to IQOS are based on a seven day assessment only,52 which limits the ability to generalise the findings as a reflection of sustained behavioural change. It is likely that the number of people who use IQOS exclusively is lower than PMI’s estimates.3 PMI’s statements are based on the assumption that current dual users of tobacco and IQOS will all give up smoking cigarettes, and that the process of “conversion” will not be reversed.353

PMI does not systematically publish raw data on the quit intentions of its users. Prior to the EU menthol ban, Philip Morris Ltd (PMI’s UK subsidiary) reported that 15% of UK consumers would try to quit in response to the ban, while over 50% would consider switching to IQOS “once made aware of this option”. It appears that this survey involved showing participants the IQOS device, but it is not known if they were shown other HTPs, e-cigarettes, smokeless tobacco or medical cessation tools, such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT).54 This finding has not been independently verified and other survey data does not support PMI’s claims. (For more details see Menthol Cigarettes: Industry Interference in the EU and UK)

Dual and poly use

Evidence suggests even low levels of ongoing smoking can be deadly.55 Thus, if HTPs are to have a potential public health benefit, they must not only reduce the risk of harm and disease compared to cigarettes and other smoked products (currently unproven), but also be used by smokers exclusively, not just ‘most of the time’.

Yet, there is emerging independent evidence of considerable dual and poly use in countries where PMI says that IQOS is helping smokers to quit cigarettes. Multiple independent studies amongst have found many HTP users also concurrently use other tobacco and nicotine products, particularly cigarettes.56575859606162 In two of these studies, the authors note their findings suggest HTPs may serve as “complements” to cigarettes rather than an aid to quitting them.5657

These patterns of dual and poly use are confirmed by PMI’s own evidence. For example, 2017 and 2019 conference posters based on PMI’s surveys in Japan identify, yet downplay, significant dual and poly use of IQOS, cigarettes and other nicotine products. 4963

Apart from this not being a representative sample of the global population, e-cigarettes are banned in Japan, meaning that IQOS has little competition from other products. As the FDA noted:

“Consumers may be more likely to try using IQOS if non‐cigarette tobacco products such as nicotine‐containing e‐cigarettes are not readily available”.19

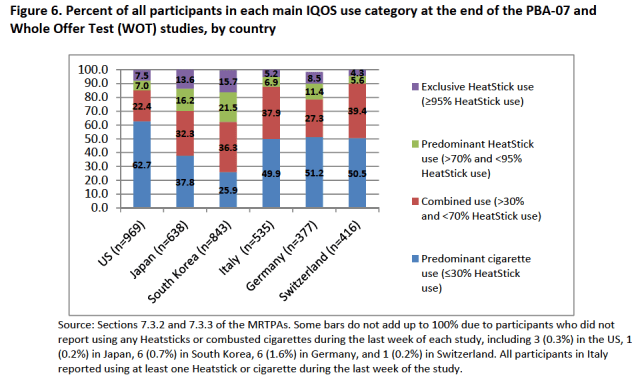

In its review, the FDA created its own chart based on PMI’s perception and behaviour studies and definitions (image 2 below). This showed that across five countries, significantly more people also used cigarettes (dual use) or reverted to cigarettes, than exclusively, or even predominantly, used IQOS.19

Image 2: FDA chart showing dual use, based on PMI’s data (Source: FDA)19

Academic review by McKelvey et al. found that PMI’s consumer perception and behaviour studies were fundamentally flawed in multiple ways: findings were extrapolated from a diary task to the whole sample, when only half of the participants had completed it; studies did not count use of other tobacco products, only cigarettes and IQOS; studies were limited to a 4-6 week period, when HeatSticks were provided for free (giving a price advantage and potential bias, meaning that the results were not representative of smokers or HTP users); and they did not allow sufficient time to identify how many IQOS users might “switch back” to cigarettes.64 In addition, the authors stated that PMI had mis-represented its own finding around participants’ quit intentions and downplayed the likelihood of dual or poly use.64

Euromonitor International (which receives project funding from the Foundation for a Smoke Free World and PMI) published a report in May 2020, which included some general findings on nicotine use from surveys it conducted in 2019 and 2020.65 In part, this survey was designed to “understand the extent and nature of dual and multiple formats”.65 The report noted that the HTP market is still relatively small, and that dual and poly use is most common among smokers who also use e-cigarettes and/or other products (which were not specified in this report). It also stated that in the case of HTPs, only 15% of users reported that they were planning to quit completely in the next year, and that this was “the smallest proportion of consumers of any category”.65 Euromonitor suggests this is due to the “immaturity” of the HTP category compared to other tobacco and nicotine product categories, such as e-cigarettes.65

Another Euromonitor report from April 2020, based on its nicotine survey, stated that around 20% of e-cigarette users planned to move to HTPs (up from 18% in 2019) and around 30% of HTP users planned to move to e-cigarettes. Given the large size of the e-cigarette market this would lead to a significant “net gain for heated tobacco”.66

For information on the global HTP market see Heated Tobacco Products

PMI is careful in public statements not to refer to IQOS users as “smokers”, even when they also smoke cigarettes. Stanford University researchers have pointed out that dual use of cigarettes and IQOS, where smoking is not allowed for example in “IQOS Friendly Places”, may in practice “serve to deepen nicotine addiction and make cessation less probable”.28

HTPs may attract non-smokers

PMI also downplays data on non-smokers who start using IQOS. In work based on its Japanese surveys, PMI states that “initiation and re-initiation of tobacco use with IQOS was minimal in both surveys and years” but does not explain how these figures were derived.49 PMI’s studies have actually found up to 2% of registered Japanese IQOS users were not nicotine or tobacco users when they started using IQOS.6749 Further, up to 6% of non-smokers and up to 15% of former smokers expressed an intention to use IQOS in PMI’s Japan and US surveys.6869 None of these studies have been published in peer-reviewed journals.

There is some evidence emerging that HTPs may be attractive to those who have never smoked cigarettes, including young people.70 While there is currently little evidence of a potential ‘gateway effect’ (i.e. people who don’t smoke or use nicotine products start using HTPs and then move onto conventional cigarettes), any tobacco or nicotine product uptake would clearly lead to an increase in harms to health.37 Research from Italy (a country where HTPs were introduced at a favourable tax rate, and a key IQOS market) found that 45% of Italy’s 740,000 IQOS users, and over half of the 1.2 million people who were expressed an intention to try IQOS, were people who had never smoked.7172 This finding was supported by research from South Korea, which found that HTPs were likely to be attractive to youth who had not previously used any tobacco products.73 The FDA noted that:

“the currently available evidence suggests that youth uptake of IQOS is currently low in countries where it has been measured. However, given that IQOS is still a relatively new product, the uptake and use patterns among youth in these markets, or any market that may start selling IQOS, is unclear”.19

Its marketing authorisation for IQOS in the US requires PMI to conduct post-market assessments to “ensure that youth exposure to tobacco marketing is being minimized”.19

Analysis of surveys conducted in Canada, England and the US, published in 2020, also found that non-smokers were interested in trying the product.74

IQOS rejected as a cessation tool

There is very little evidence that IQOS is effective as a quit tool at the individual level or population level. A 2022 Cochrane review of the evidence on HTPs for cessation concluded:

“Heated tobacco probably exposes people to fewer toxins than cigarettes, but possibly more than not using any tobacco. Falls in cigarette sales appeared to speed up following the launch of heated tobacco in Japan, but we are uncertain whether this is caused by people switching from cigarettes to heated tobacco”.75

New Zealand

When instructing public health officials to reject PMI’s offer of free IQOS in August 2019, the Director-General of Health stated that “the health sector does not share the same goals or aspirations of this industry”.16 He also referred to PMI’s funding of FSFW, and discouraged engagement with COREISS, stating that “there is a range of alternative sources of information and advice on smoking cessation and the possible use of vaping products to support cessation, including for Māori”.16

Australia

Despite intense lobbying by PMI to allow the sale of IQOS, in August 2020, the Australian government’s Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) rejected the sale of HTPs in Australia.7677.

The TGA found that PMI’s assertion that smoking rates in Australia had “stagnated” was inaccurate, and that rates were in fact continuing to decline. In addition to uncertainty over nicotine levels and general health risks (which included PMI’s own research findings), the TGA also highlighted the concern that HTPs might still attract people who had never smoked, including youth: “there would be no ability to restrict the supply of HTPs to smokers seeking to quit”.76

In Australia, nicotine products, including HTPs, are available via a medical prescription for smoking cessation. The TGA concluded that as a consequence, there was no justification to introduce “a new nicotine product for non-therapeutic use”.76

Mexico

In September 2020, the Mexican Ministry of Health reaffirmed the ban on the import of HTPs, made clear that IQOS had not been granted any form of reduced risk status in Mexico and stated that it did not support its use as a tool to stop smoking.78 For more information see: Heated Tobacco Products

Why does this matter?

TCRG researchers have stated that until the relative health risks are determined, HTPs, including IQOS, have no public health role:22

“There is currently no evidence that IQOS helps smokers quit. Smokers wishing to quit should use products shown to be safe and effective in line with national and international guidance.”2179

PMI’s attempts to establish or take over cessation programmes could have a damaging effect on public health. Writing about Philip Morris’s historical efforts, MacDaniel et al concluded that:

“Such endeavors have the potential to inflict real harm by competing with more effective programs and by helping to maintain a tobacco-favorable policy environment. If PM truly wanted to support cessation, it could drop legal and other challenges to public policies that discourage smoking.”4

In 2023, the same statement can be applied to PMI.

Relevant Links

- Addiction at any cost: Philip Morris International Uncovered, Stopping Tobacco Organisations and Products/Tobacco Control Research Group, 2020

- STOP/TCRG, FDA does not rule that IQOS reduces tobacco-related harm, yet PMI still claims victory, Issue brief, July 2020

- WHO statement on heated tobacco products and the US FDA decision regarding IQOS, July 2020

TobaccoTactics Resources

- Harm Reduction

- Heated Tobacco Products

- Newer Nicotine and Tobacco Products: Philip Morris International

- PMI Promotion of IQOS Using FDA MRTP Order

TCRG Research

- Tobacco industry messaging around harm: Narrative framing in PMI and BAT press releases and annual reports 2011 to 2021, I. Fitzpatrick, S. Dance, K. Silver, M. Violini, T.R. Hird, Frontiers in Public Health, 18 October 2022. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.958354

- Corporate communication of the relative health risks of IQOS through a webchat service, S. Braznell, J.R. Branston, A.B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, Online First: 03 March 2022. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056999

- PMI New Zealand conflates IQOS heated tobacco products with electronic nicotine delivery systems, L. Robertson, J. Hoek, K. Silver, Tobacco Control Published Online First: 19 November 2021. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056964

- US regulator adds to confusion around heated tobacco products, A.B. Gilmore, S. Braznell, BMJ, 2020;370:m3528

- Understanding the emergence of the tobacco industry’s use of the term tobacco harm reduction in order to inform public health policy, S. Peeters, A. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2015,24(2):182-189

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to TCRG publications.