Tobacco Industry Pricing Strategies

This page was last edited on at

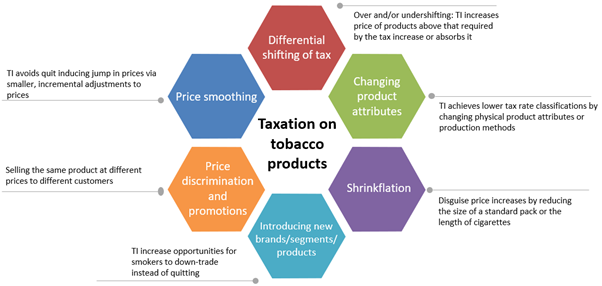

A review study carried out in 2021 by the Tobacco Control Research Group, found that the industry utilises six broad pricing strategies in order to undermine the effect of tobacco taxation. 12 These are used in both high income countries (HICs) and low and middle-income countries (LMICs) and are summarised in figure 1.3

Figure 1: Tobacco Industry Pricing Strategies (TCRG original research)

Here we describe each strategy with examples from HICs and LMICs.

- See also the Price and Tax main page.

Differential shifting of taxes

Instead of fully passing on the taxes on tobacco products to consumers, the industry may decide to shift taxes to different brands and/or different tobacco products:

- Overshifting: takes place when the TI increases the price of products above that required by the tax increase. The burden of the tax increase (and more) falls entirely on the consumers rather than the producers.

- Undershifting: occurs when the industry absorbs tax increases (to some extent), thus delaying/preventing the intended tobacco price rises. In this scenario, the producers bear at least part of the cost of the tax increase. This is one of the most frequently employed pricing strategies of the industry and has been identified in multiple countries worldwide.

Differential shifting of taxes is the most frequently employed strategy of the tobacco industry (TI). In many HICs, the TI persistently increases tobacco prices by overshifting tax increases on on premium products (those at the higher end of the market) but undershifting on ‘budget’ products (in the lowest price segments) in order to keep their prices low. This results in an increasing price gap between premium and budget products. This pattern has been observed in the UK,45 Ireland,6 and several other European countries;7 the US;8910 and New Zealand.1112.

In contrast to HICs, undershifting is a more commonly used tactic in LMICs, as witnessed in South Africa,13 Mexico,1415 Indonesia,16 Turkey,17 Thailand,18 Bangladesh,19 Pakistan,20 and Mauritius.21

Research in LMICs has highlighted that tobacco companies in these countries deliberately chose to undershift their products. Their primary goal appears to be expanding their markets as opposed to increasing their profits. Therefore, tax increases are mostly absorbed by the tobacco companies for brands across all price categories.

This pattern varies slightly in China, which is a state-owned tobacco monopoly market, and the state has a pivotal role in setting both prices and taxes. Between 2009 and 2015, the state decided against increasing prices, which resulted in reduced profits for the industry. However there were no changes in the rates of cigarette consumption.22

There is evidence to suggest that when the near-monopoly environment of the tobacco industry is under threat from changes in market dynamics (e.g. from legal or illicit low-cost providers) this will also change the observed industry pricing strategies over time. For example, in South Africa there was a switch from overshifting to undershifting in 2010, which coincided with increased competition from domestic low-cost producers and a rapid increase in illicit trade.23

Evidence also indicates that tobacco manufacturers tend to absorb smaller tax increases, while larger increases in tax rates force them to raise their prices in order to maintain profits. 2425

Introducing new brands, segments or products

It has been observed that in markets where multiple types of tobacco products are available, the increase in taxes on one product can encourage consumers to substitute or down-trade to cheaper alternative products, such as roll-your-own (RYO). This consumer behaviour has been observed in the UK,262728 Spain,29 and Thailand,18, as a result of the tobacco industry’s launch of cheaper substitutes.

These include new and cheaper factory made (FM) as well as RYO products, including cheaper variants of existing products and new price segments, and increase the opportunities for smokers to down-trade instead of quitting. In some countries, this tactic is used to target women and young people.28 This industry strategy helps retain customers who no longer want, or are unable, to pay for higher priced products. At the same time, they continue to offer premium products that allow the industry to profit from those who are willing to pay higher prices for ‘luxury’ brands.

There is evidence of similar brand substitution in Bangladesh between 2006-2017.19 At the same time there was also a shift from bidis to FM cigarettes, indicating growth in people’s incomes and shifting preferences.19 Therefore, the manufacturers of tobacco created two different pathways for consumer to maintain sales volumes and profitability: by offering low-priced cigarettes, they generated new sales by encouraging a shift from bidis (which are generally independently made and very low priced); and low-priced FM offered smokers of premium cigarettes a cheaper option instead of quitting.

Price discrimination and price related promotions

Selling the same product at different prices to different customers, often through targeted price-related promotions, can keep products affordable across all income groups following a tax increase. This helps to prevent price-sensitive users from quitting or reducing consumption, ensures potential new customers are not deterred by high prices, but allows the industry to take advantage of those less sensitive to price.

Evidence from the US, Canada and the UK, highlights the industry’s targeted promotional activities.30 These are targeted at price-sensitive consumers with certain products discounted through coupons, bulk purchase offers on cartons, or free gifts. Different prices of the same product are also offered to consumers in different store types and locations, such as Native American reservations in the US and Canada.313233 As a result, smokers are able to avoid the full impact of taxes by buying cartons or purchasing from lower tax jurisdictions. This strategy is also beneficial for the tobacco industry as it maximises their profits by minimising the effect of tax increases.34

Price smoothing

Following tax increases, tobacco companies ‘smooth’ price by implementing price rises throughout the year by employing smaller, more frequent increases. This ensures that smokers never face a sudden, large, price increase, which could encourage quitting. Therefore, this effectively minimises the public health impact of tax increases. This strategy has been used in the UK, alongside undershifting.35 The smoothing period was longer for cheaper product categories of FM, rather than RYO tobacco.2826

Shrinkflation

Companies may reduce, or ‘shrink’, the number of sticks in a pack from, or the weight of tobacco per pack. This disguises price rises and prevents the cost of a packet of tobacco from being tipped over a certain psychological level. The higher cost per cigarette does not become immediately obvious to most smokers. In the UK, tobacco manufacturers masked price increases by charging the same pack prices that were charged before the tax increase. This was achieved by reducing the size of a FM pack from the standard 20 sticks to 19, 18 or even 17 sticks per pack and the size of a RYO pouch of tobacco from the typical 12.5 to 10 grams.26 This strategy was more common in the ‘budget’ and mid-priced products. Thus, despite the rise in price per stick, the real pack prices of the cheapest FM and RYO products remained static in the UK between 2012 and 2017.28

Changing product attributes or production processes

The industry can exploit tobacco tax structures that levy different tax rates based on different product characteristics (e.g. length, weight, price, or product type). Companies may change the physical attributes of their products, or alter the production methods, in order to achieve lower tax rate brackets or categories.

In the UK, cigars were subject to relatively lower taxation than cigarettes and exempt from some of the restrictions covering all of the European Union (EU).26Tobacco companies took advantage of these differences in legislation by launching economy cigars and low-priced cigarette-like filtered cigarillo products from 2010.36 Marketing under existing cigarette brand names in 2020 helped them to circumvent the EU menthol ban.36

Tobacco companies may also effectively reclassify their own products in order to avoid higher taxes. In the US, from 2009 to 2013, tax on RYO tobacco was higher than for pipe tobacco – so the industry relabelled RYO as pipe tobacco, reducing its tax liability. As a result, sales of RYO tobacco fell while sales of pipe tobacco increased.3738

It has been argued that a complex taxation system, with differential tax rates for each type of product, favours this pricing strategy. For example, up until 2009, Indonesia had an elaborate multitiered tax system, with varied tax by different product types (such as cigarette or kretek), by mode of production as well as by the manufacturing facilities. This favoured smaller scale production facilities, and provided a tax incentive for companies to split production between large numbers of small-scale producers.39

TobaccoTactics Resources

Menthol Cigarettes: Industry Interference in the EU and UK

Relevant Links

The Price We Pay: Six Industry Pricing Strategies That Undermine Life-Saving Tobacco Taxes, STOP report, exposetobacco.org

Video in English, Urdu and Indonesian

TCRG Research

How has the tobacco industry passed tax changes through to consumers in 12 sub-Saharan African countries? Z.D. Sheikh, J.R. Branston, K. Zee, A.B Gilmore, Tobacco Control Published Online First: 11 August 2023, doi: 10.1136/tc-2023-058054

Tobacco industry pricing strategies for single cigarettes and multistick packs after excise tax increases in Colombia, Z.D. Sheikh, J.R Branston, B.A. Llorente et al, Tobacco Control, Published Online First: 31 May 2022, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2022-057333

Tobacco industry pricing strategies in response to excise tax policies: a systematic review, Z.D. Sheikh, J.R. Branston, A.B Gilmore, Tobacco Control, Published Online First: 09 August 2021, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056630

Impact of tobacco tax increases and industry pricing on smoking behaviours and inequalities: a mixed-methods study, T.H. Partos, R. Hiscock, A.B. Gilmore, et al, Public Health Research, April 2020, 8(6):1-74, doi:10.3310/phr08060

Standardised packaging, minimum excise tax, and RYO focussed Tax rise implications for UK tobacco pricing, R. Hiscock, N.H. Augustin, J.R. Branston, A.B. Gilmore, PLoS One, February 2020, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228069

Cigarette-like cigarillo introduced to bypass taxation, standardised packaging, minimum pack sizes, and menthol ban in the UK, J.R. Branston, R. Hiscock, K. Silver, et al, Tobacco Control, August 2020, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055700

Tobacco industry strategies undermine government tax policy: evidence from commercial data, R. Hiscock, J.R. Branston, A. McNeill, et al , Tobacco Control, 2018, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2017-053891

Tobacco industry strategies to keep tobacco prices low: evidence from industry data, A. Gilmore, R. Hiscock, R. Branston et al, Tobacco Induced Diseases, 2018;16(1):115. doi:10.18332/tid/84000

Understanding tobacco industry pricing strategy and whether it undermines tobacco tax policy: the example of the UK cigarette market, A.B. Gilmore, B. Tavakoly, G. Taylor, H. Reed, Addiction, July 2013, doi: 10.1111/add.12159

UK tobacco price increases: driven by industry or public health?, R. Hiscock, J.R. Branston, T.R. Partos, A. McNeill, S. C. Hitchman, A.B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2019, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-054969

Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: an analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials, A.B Gilmore, Tobacco Control 2012, doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050397

What is known about tobacco industry efforts to influence tobacco tax? A systematic review of empirical studies, K.E. Smith, E. Savell, A.B. Gilmore, Tobacco Control 2013, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050098

For a comprehensive list of all TCRG publications, including research that evaluates the impact of public health policy, go to TCRG publications.